Assam’s Illegal Immigration Crisis – An Existential Threat

At the very outset, it needs to be emphasised here that the problem of illegal immigration in Assam from across the border with Bangladesh is a serious political, economic, and demographic issue and not a communal one. In fact, it is more a matter of saving a community’s cultural and civilisational pride, and not simply its religious identity.

Our ancestors had resisted tooth and nail all attempts to be dominated by any force alien to their history and culture. But, unfortunately, a defeatist mentality of choosing political correctness over raising the truth seems to have now infested the Hindu psyche to the extent that a stark political and socio-economic reality has become a monstrous one with the passage of time! It is now no longer a war of swords and weapons unlike in the times of Mahmud of Ghazni or Muhammd Ghori, but has become a demographic war of numbers.

The policy of Lebensraum has often been quoted publicly by several Bangladeshi academics and political leaders on numerous occasions. Although not much has been specified as to how exactly it will happen, but they have given enough hints on how it is to be possibly executed. In his work ‘The Myth of Independence’, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto writes,

“It would be wrong to think that Kashmir is the only dispute that divides India and Pakistan, though undoubtedly it is the most significant one. One at least is nearly as important as the Kashmir dispute, that of Assam and some districts of India adjacent to East Pakistan. To these Pakistan has very good claims.”

Sheikh Mujibur Rehman, the founding-father of Bangladesh, clearly wrote in his booklet Eastern Pakistan: Its Population and Economics,

“Because Eastern Pakistan must have sufficient land for its expansion and because Assam has abundant forests and mineral resources, coal, petroleum, etc. Eastern Pakistan must include Assam to be financially and economically strong.”

An analysis of the history of India-Bangladesh relations brings to light the fact that India had extensively supported and provided all possible help to Sheikh Mujibur Rehman of then East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) who was at the forefront of the liberation war. Nevertheless, no matter how friendly India’s relations with Bangladesh might be, it would be too naïve to ignore the dangers of large-scale illegal migration from Bangladesh over several decades. It has not only gradually altered the demographic profile of the state of Assam, especially in the border districts of Lower Assam, but also poses a grave existential threat to the people and their culture and most importantly, to India’s national security.

Although Assam has always been a land enriched by successive waves of migration and migrants, the peculiarity of the migration problem here predominantly began in the late 19th century. It was around this time that the Assamese had started employing cheap labour from the surrounding regions, especially Bengal (now Bangladesh), to work in their farms and agricultural fields.

The discovery of tea in Assam resulted in populating the state with tribals brought in from the Chhotanagpur region to work as labourers in the large British-owned tea estates. Gradually, migrants looking for job prospects in the North-eastern oil-fields were naturally attracted to the region. The British also encouraged Bengali Muslim peasants from present-day Bangladesh to move into Lower Assam for putting virgin land under cultivation.

During Sadullah’s Muslim League Ministry in Assam (1937-46), a concerted effort was being made to encourage the wholesale migration of Bangladeshi Muslims into Assam chiefly for nourishing a political vote-bank. After partition, the porosity of the Bangladesh-Assam border allowed unabated migration for the next several decades. Between the years 1947-1971, Assam saw two big waves of refugee influx. A continuous stream of politically victimised minorities, majority being Bengali-speaking Hindus from East Pakistan, were also coming and settling down in the Brahmaputra Valley.

While the Muslim migrants from East Pakistan were mostly landless economic refugees, the Bengali Hindu refugees were mainly the victims of political and religious persecution in a monotheistic theocratic state. The latter were largely from Sylhet, which had become a part of Pakistan at the time of Independence. Since they were ostracised in their own native lands for professing a particular faith, they later migrated into the adjoining areas of the Barak Valley, such as Cachar, Karimganj and Hailakandi.

By now, a deep sense of insecurity had already been created in the minds of the common public of Assam with respect to the alarming demographic change as a result of the large-scale influx of Bengali migrants. The issue of immigration has been a deeply complex and sensitive one in the identity politics of Assam. It eventually culminated in the Assam Movement (1979-85) led by the AASU.

One of the largest public mobilisations ever witnessed in post-Independent India, the Assam Movement began from the Mangaldoi Lok Sabha constituency in 1979 due to a sudden increase in the population of the electorate by a whopping 80,000 voters within a span of just one year. The then Golap Borbora-led state government under the Janata Party accused the Congress Party of having ‘imported’ nearly 70,000 Bangladeshi Muslim refugees purely for electoral gains. Subsequently, the term ‘illegal Bangladeshis’ entered the lexicon of Indian politics, having significant electoral and strategic connotations for understanding the different manifestations of Assamese identity politics at different junctures in history.

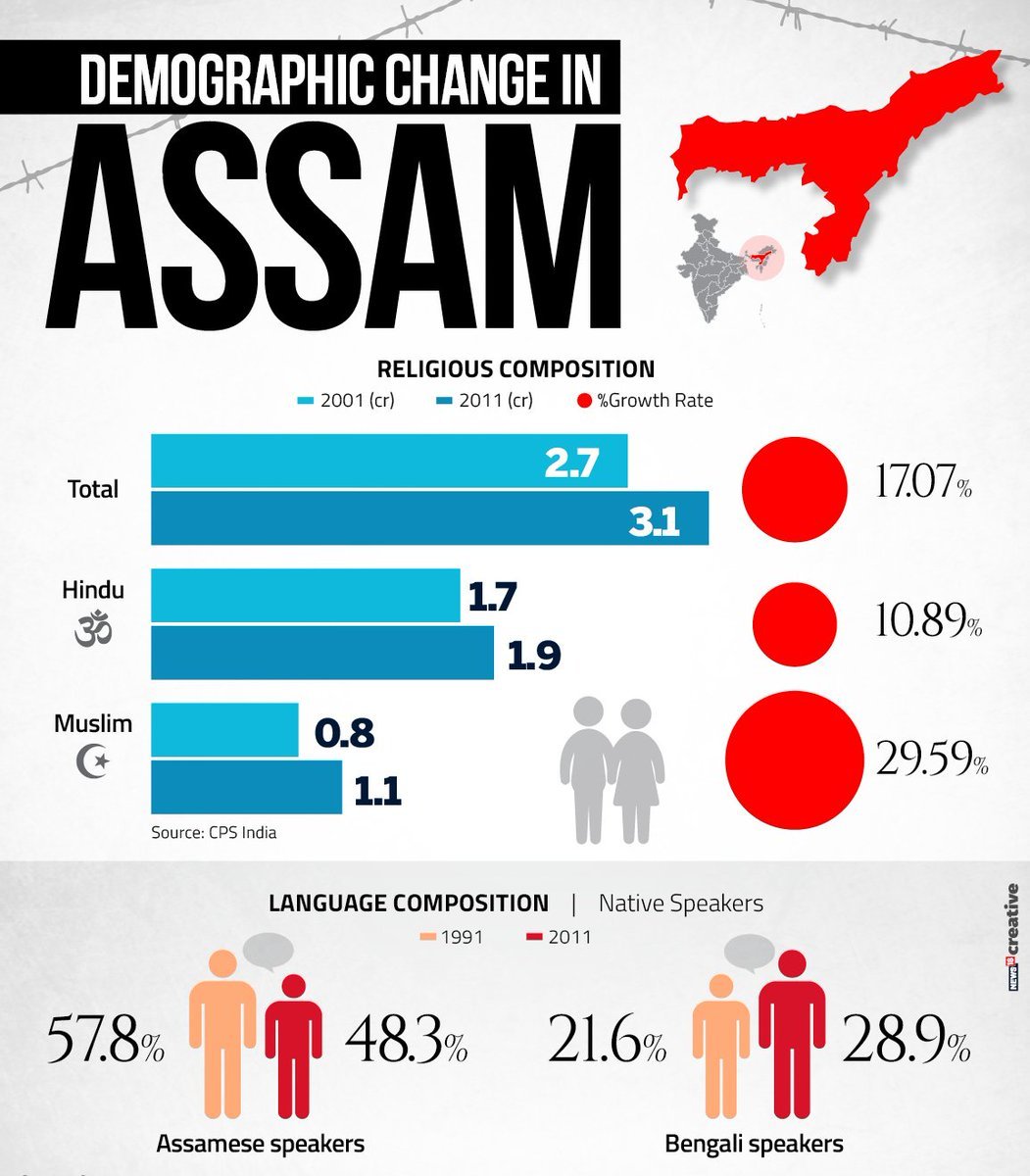

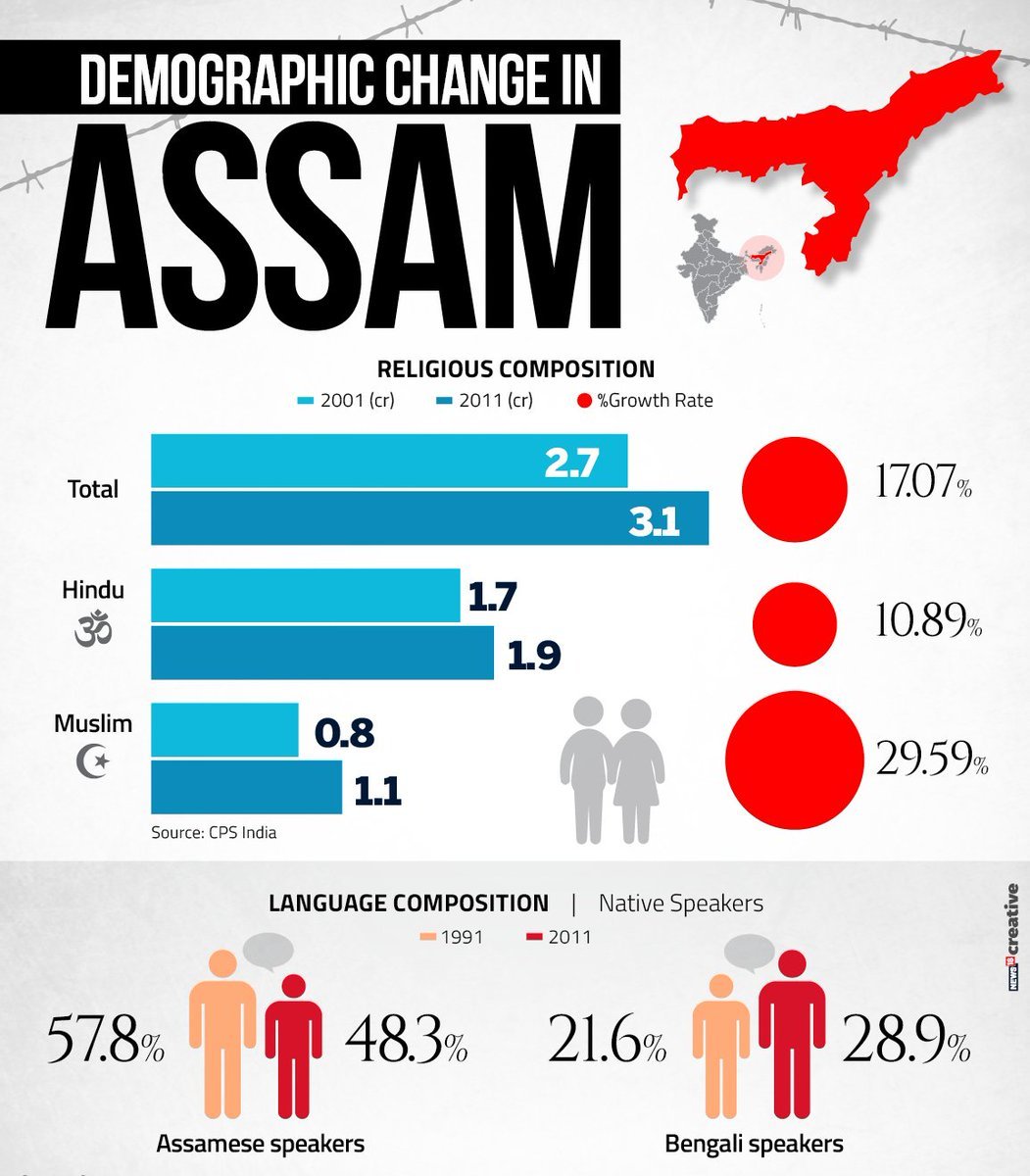

The Census data of 2011 reveals a steep rise in the migrant population in nine border districts of Assam. While Muslims constituted 30.9% of the population in 2001, this share jumped to 34.2% in 2011. A Report on ‘Illegal Migration into Assam’ submitted to the President of India by the then Governor of Assam Lt. Gen (Retd.) S.K. Sinha in 1998 clearly showed that the Muslim population of Assam rose by 77.42% in 1991 from what it was in 1971. Comparatively, in the same period, the Hindu population had risen by a mere 41.89%. Among the several eye-witness accounts that had been provided by the report, one stands out particularly (quoted from the report):

Shri E.N. Rammohan, DG. BSF, who is an IPS officer of the Assam cadre, in his report of 10 February, 1997 has stated, “As an additional S.P. in 1968 in Nowgaon, I did not see a single Bangladeshi village in Jagiroad or in Kaziranga. In 1982, when I was posted as DIGP, Northern Range, Tezpur, five new Bangladeshi Muslim villages had come up near Jagiroad and hundreds of families had built up their huts encroaching into the land of the Kaziranga Game Sanctuary.” He mentioned that in 1971, the large island of Chawlkhowa comprising 5000 bighas of land was being cultivated by Assamese villagers from Gorukhut and Sanuna and went on to state, “In 1982, when I was posted as DIGP, Tezpur, there was a population of more than 10,000 immigrant Muslims on the island. The pleas of the Assamese villagers to the district administration to evict those people from the island fell on deaf ears. Any honest, young IAS, SDO of Mangaldoi sub-division who tried to do this, found himself transferred. In 1983 when an election was forced on the people of Assam…the people of the villages living on the banks of the Brahmaputra opposite Chawlkhowa attacked the encroachers of this island, when they found that they had been given voting rights by the Government. It is of interest that the Assamese Muslims of Sanuna village attacked the Bengali Muslim encroachers on this island. I am a direct witness to this.”

Whether self-professed ‘liberals’ or ‘secularists’ might agree or not, but the rise to power of Maulana Badruddin Ajmal in the political scenario of Assam has largely been aided by the rapidly changing demographic character of the state. The gradual reach and expansion of his party – the All India United Democratic Front (AIUDF) – both in terms of vote-share and seat-share, is a proof of the fact.

While there is still lack of credible data and reliable figures on the exact number of Bangladeshi nationals staying in India illegally, there is no doubt that the flow of illegal immigrants continues unabated. On November 16, 2016, Kiren Rijiju, Union Minister for Home Affairs stated in the Rajya Sabha that an estimated 20 million illegal Bangladeshi migrants are staying in entire India; and, most of these migrants are said to have settled in Assam and West Bengal while many have moved into the interiors of the country, even reaching metropolitan cities like Delhi and Mumbai in many instances. Undocumented Bangladeshi migrants are largely uneducated, and generally occupy the lowest rungs of the labour force.

Besides the threat of demographic change as a result of illegal immigration, another serious danger looming large not only over Assam but that of the entire country is of a “second partition” with the complete or partial loss of Lower Assam to Bangladesh, aided and abetted by international Islamic terrorist groups and their sponsors such as Pakistan’s ISI. In the words of S.K. Sinha himself, the former Governor of Assam,

“The rapid growth of international Islamic fundamentalism may provide the main driving force for this demand. The loss of Lower Assam will sever the entire North-East from the rest of India and the rich natural resources of that region will be lost thereafter.”

Although a great deal of misinformation had been spread by a paid, agenda-driven media during the anti-CAA protests in Assam, but certain genuine Assamese concerns regarding language and resources over the CAA cannot be ignored. At the same time, the scourge of increasing illegal migration of people largely belonging to one particular religious community is also a real-time danger. In Tripura, the local tribals of the erstwhile princely state became a minority in their own land due to a huge influx of Bengali-speaking migrants from what is now Bangladesh, at the time of India’s Partition in 1947. This was being held up as a cautionary tale by Assam during the anti-CAA protests. For the BJP and its allies, the need of the hour is a strong political will backed by an effective implementation machinery to address the issue, without, however, exploiting the raw sentiments of the people for electoral mandates.

References:

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text.