Government Control of Temples – What Next?

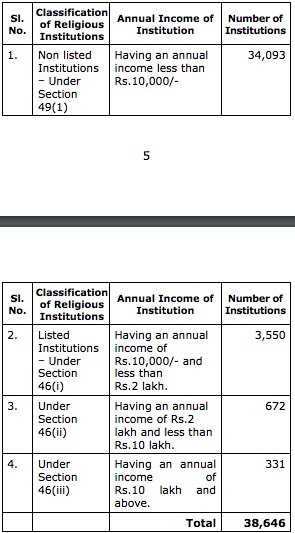

While one can wish away Government control of Hindu Temples, it's not such easy a proposition to find an answer. Which one is better? A better management of temple under government control or a private management for a temple?