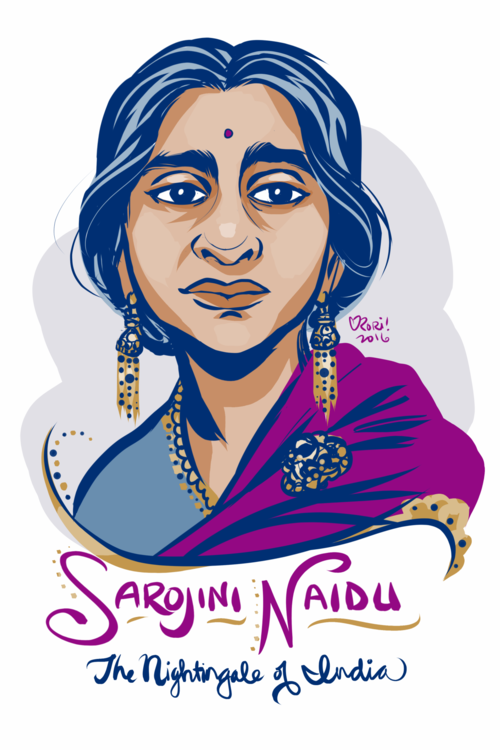

Sarojini Naidu: A Poet Forgotten

Makarand Paranjape, poet, scholar, researcher, teacher, has performed a stellar service in compiling her selected poetry and prose, with detailed commentary about her challenges, needs, roles and burdens as one of the early Indian poets in English, strutting the ramp for western audience and the literati.