Cultural Majesty, Political Dinge

The General was back at his residence, and he sat in his specially built library reading a book, sipping fine digestif after an early dinner.

The door to his library flung open and was shut with equal tempest. But the General was not startled. “I see something has agitated you, dear boy,” he said, his voice nonchalant, his eyes still trained on the book. It was his secretary; young, athletic, his flowing hair the black of night.

An air of agitation was about him. “How could they?” he asked. “How are we suddenly the instruments of a political party? Do we not swear by the Union, by the Constitution, by the non-partisan office of the President?”

The General looked up from his book, his face matter-of-fact. “You seem to have stumbled upon a fairly unique variant of mules who dwell in the utter depths of a cesspit of turpitude. For convenience and courtesy, we call them parliamentarians; and in the august chambers of their office, they do some very unparliamentary things indeed.”

The secretary stared at his boss, feeling muddled for a moment. His agitation had not allowed him immediately to imbibe the General’s words. But he soon picked up the train of thought. “Yes, I am referring to them,” he said, his agitation steadily dissipating, but not his sense of chagrin.

“I believe you have in mind, more specifically, their latest minstrelsy of disfavour anent some military operation that we undertook in the past, and which became controversial after the dust of contemporaneous passion had settled,” the General said, stressing the first adjective in a sardonic fashion.

“I do indeed,” the secretary confirmed. “But, on this occasion, it is the ruling party that has done so! The same party that, so far, maintained at least the appearance of concern for national security! And now, it has denounced an aerial offensive that we undertook in our territory a few decades ago, in a region that was rife with subversive strength. And they had the gall to describe us as the ‘air force of the then ruling party’ that struck its own citizens, when we did nothing of that sort!”

Sometimes, even other branches of the military became imbued with a uniform consciousness of being ‘the Armed Forces’ whenever one branch became a weapon in political pugilism by one party against another.

The General had to think but for a moment. “I know what operation it is to which you refer.”

“Why can there be no unanimity of opinion in the political class on such operations as have so heavily borne on our security?” the secretary asked, feeling distressed.

“Dear boy, unanimity is to be expected from those who treat our nationhood not as a matter of mere constitutional device, or a conglomerate of constituencies to be looted, but from those who spiritedly believe in it,” the General said, his voice stentorian, but also strangely soothing.

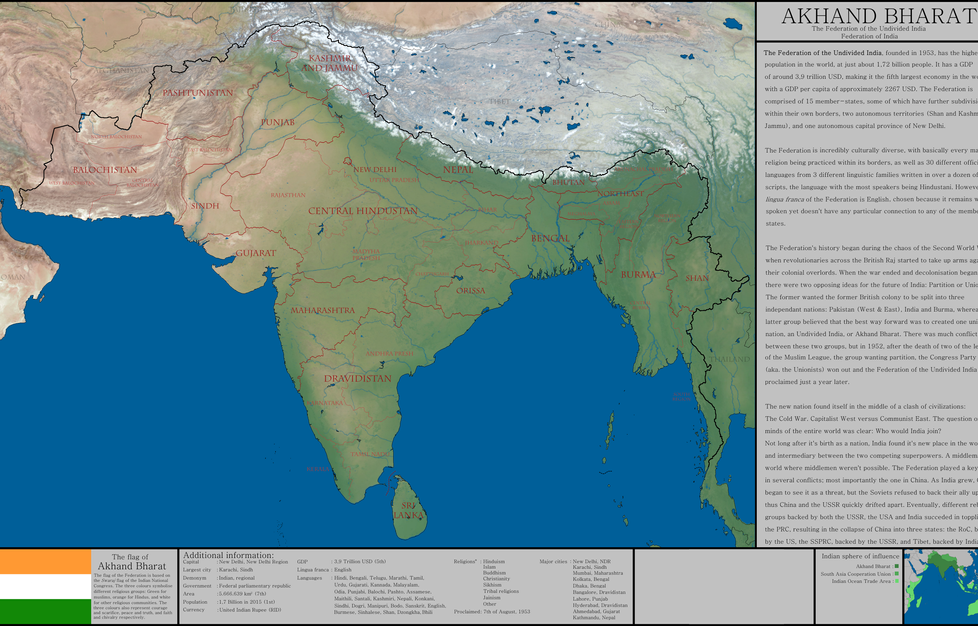

“How is there no belief yet? Did our independence struggle not make us a living, breathing nation before the Constitution came into force? Did the beacons of our freedom struggle themselves not invoke our ancient and enduring cultural oneness from our frontiers facing Parshvasthana in the West to our frontiers facing the Middle Kingdom in the East; from the Great Mountains in the North to the Great Ocean in the South? Never mind the eventual abridgment of territory; is our immemorial antiquity to have no worth?”

It was rather easy for the General to answer this. “The word you used is ‘cultural’, dear boy. ‘Cul-tu-ral’. It implies the existence of a culture, of civilizational consciousness. The word ‘politics’ very often stands in opposition to ‘culture’. Do you truly suppose a bunch of clodhoppers understand such notions? But how discourteous of me to keep you standing! Do be seated!”

The secretary sat in a chair across the table. The General poured him some claret, and added a generous dose of diet Pepsi to it. “A considerably diluted filling for you, young man.” The secretary did not mind. He was much more abstemious than his boss — whose senses never seemed dulled by the drink — and partook, only with some reluctance, of such rich potations.

“It occurs to me,” the General said, subconsciously moving his demitasse in elegantly infrequent motions, “that, despite occasional overlaps, the realms of culture and politics are rather distinct. The former encourages rich literature, music, epistemology, philosophy, and architecture; the latter encourages insipidity, cacophony, ignorance, decadence, and squalor. The former has epics and gods who guide civilization and uphold selfless heroism; the latter has manifestoes of petulance and false gods who care little for civilization. And how utterly it holds true of our country, where glib speech has long been a substitute for action! It does not matter what you actually do for the downtrodden; it matters how eloquent and passionate are your hymns of hate against imagined oppressors. You have in our country a congeries of groups claiming such distress. C’est une république de victimisation compétitive.”

The secretary seemed astonished; but his astonishment was of a kind that marvelled more at the adroit tool that dug than at the treasure the tool’s use discovered. He knew this all along, but he needed someone to say it aloud.

“The logical result of this,” the General went on, “is that there is much nationhood in letter and little in spirit. You have, therefore, no calm entities with different ways of solving a problem; you have obstreperous mules who fight like cats and dogs. In this fight, everyone below them is expendable. And since we in the military answer to the civilian bosses, we may sometimes be used as matériel, too.”

“Then there is no hope, is there?”

“We should not lay claim to omniscience. The ways of history are mysterious. A cunning force of rectitude may well rise and restore this nation to a proper station. But it is not for us to undertake. So, serve dutifully, sip fine wine, and sleep soundly.”

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text.