Baseless Solidarity and a Surprised Pikachu-face in the Storm of Hate

Over the past few months, we have been witness to a deluge of hate against Indians, particularly Hindus, on such platforms as Twitter. But while the sad chambers of online racism must bear the lion’s share of the blame for this, there can be little exoneration of ourselves in having furnished a cause.

To develop fondness for a country on account of one’s experiences differs from a cloying, oleaginous investment in its fate. This sharp distinction seems to elude us Indians. Be it the Israel-Palestine conflict or the Russia-Ukraine War, we take with celerity to polarizing ourselves. The tenacity with which we take up cudgels on behalf of either side in a conflict may well surprise the belligerents themselves.

“Israel is not just a country; it is an emotion,” tweet some Indians, having taken permanent leave of their senses. No group articulates this but the self-proclaimed Indian nationalists. Why ought any country besides India to be such an intense emotion for any Indian nationalist? A moment of calm reflection will suggest that the wave of nationalism which swept India as social media gained momentum and Modi rose to power, must surely be very superficial, given that it limits itself to trappings and does not extend to the substance.

The same applies to those Indians who never have the time to speak for the butchered Hindus of Pakistan and Bangladesh, but have all the time in the world to call for freeing Palestine. Of late, they have even begun enthusiastically chanting, “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free.” It is a heady slogan that has corroded all reason. At first, there was in these quarters a studied silence when Hindus were butchered. Now they have lumped themselves with the deplorables who insist that Hinduphobia is not real; that no Hindus are being hewed anywhere. Apathy has mutated into antipathy; the headiness of ‘the cause’ has irremediably blackened their hearts.

This stems, I believe, from farcical notions of solidarity. International relations is an arena of ruthless pursuit of self-interest. No more than a contractual arrangement guides countries; and should national interest so demand, a country will not hesitate to foment unrest in another country, though both be bound by an alliance. No alert eye is a stranger to the hushed suggestions that some of our allies, historical or current, have been involved in buying out the national cabinet or in stoking the flames of discord in the North-Eastern regions of India. It is difficult to dismiss this as a mere canard, unless guided by sentimentality. A researcher worth his salt would relate the probabilities of such claims, disillusioning to the credulous and to the mawkish.

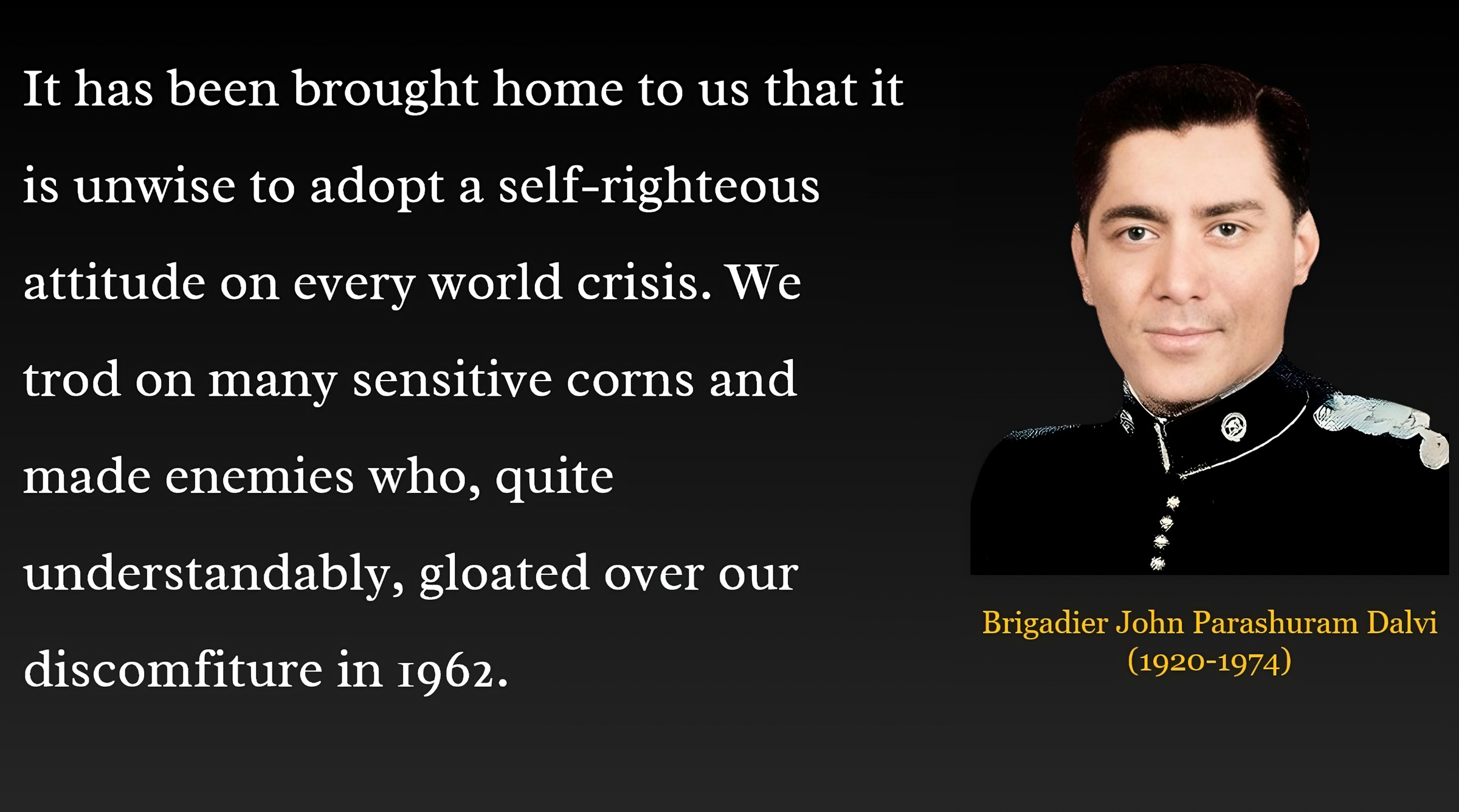

Perhaps the best book that excoriates such sentimentality is the classic “Himalayan Blunder: The Curtain Raiser to the Sino-Indian War of 1962 — The Angry Truth about India’s Most Crushing Military Disaster” by Brigadier John Dalvi (1920-1974). Though many a magisterial volume on the 1962 war have since been authored, Brigadier Dalvi’s book remains a classic.

In it he notes, among many things, how nearly all strategic thinking at the level of government had been infected with flawed idealism. Writes Dalvi:

After the painful lesson of 1962 we have come to realize that the world role of a nation is related to its power. We have realized that there is no place for policies based on flimsy notions of fellowship with coloured ex-colonial countries. The Afro-Asian concept is at best a tenuous link. The reaction of the so-called non-aligned Afro-Asian group initially shocked us and later was a major sobering factor in the post-China War reappraisal. Only Emperor Hailie Selassie of Ethiopia and Tunku Abdul Rahman of Malaysia came out openly in our favour and condemned the Chinese attack unequivocally.

He writes further:

It has been brought home to us that it is unwise to adopt a self-righteous attitude on every world crisis. We trod on many sensitive corns and made enemies who, quite understandably, gloated over our discomfiture in 1962. It is good to note that Indian spokesmen now do not express opinions on each and every international issue and gratuitously offer a solution, or mediation, or a peacekeeping contingent. We have learnt what has been common knowledge for over 2,500 years ago when a Greek sage said: “You know as well as we do that right as the world goes, is only in question for equals in power: the strong do what they can, the weak suffer what they must.”

The government learnt its lesson in 1962, but the lesson is yet to percolate down to the masses. We do not agitate for our own civilizational brethren, namely the Hindus in Pakistan and Bangladesh, but become trenchant in championing the causes of distant realms, of whose intricate histories we are likely to be ignorant. We do not so much as care to clear the fog of disinformation emanating from both sides. Such is the abattoir in which we sacrifice our self-respect. Little would any other race in the world respect us Hindus when we maintain disinterest in our identity, become intellectual belligerents in a fight not our own, and imitate the sensibilities of others. Need it surprise us that strong opinions in fights not our own would amount to the same treading over sensitive corns to which Brigadier Dalvi referred?

The least we can do is actually start thinking as Hindus as opposed to spouting high-flown claptrap about civilizational resurgence and cultural heritage, without caring to inquire what it entails. Such a thing can be very controversial, because it would require confrontation with hard facts. Perhaps the epitome of acceptance of hard facts is the plain, no-nonsense observation by Swami Vivekananda: “And then every man going out of the Hindu pale is not only a man less, but an enemy more.” To say this today would require immense mettle; to hear this would cause heartburns among cosmopolitans whose Hindu identity is merely an accident of birth. History knows no race, and may never know a race, so bold in steering away from controversial truths as that of the Hindus. Nor does any other race so passionately steer a collision course with comforting lies and resolute refusal to learn from history.

Here I must clarify that I do not propose an outlook of hate; only one of pragmatism. Seldom are Hindus actuated by hate; to the point of fearing that advocacy of concerns as a group may amount to hating another group. I implore that no such erroneous notions be entertained.

I call to mind the distinction between a ‘liberal’ and a ‘nationalist’ as conceived by John Mearsheimer. A liberal is someone who believes that the truest entity is an individual, and society is merely the result of contracts between individuals. A nationalist is someone who believes that individuals are born into communities, and that within the bounds of fidelity to community he is to carve out space for his individuality. Without the least hesitation Mearsheimer declares that nationalists are correct and that liberals are wrong.

It is my submission that Hindus behave mostly like liberals. Other than on self-defeating questions such as caste, Hindu parents do not generally raise their children with any doctrinaire love of a community-centric creed (nor, I hasten to add, is even caste a factor for the urban ‘upper-caste’ folk). They instead encourage rational thinking.

Such a thing is not a vice by itself. But because it is taken to the extreme, it slackens consciousness among Hindus as being part of the larger community. The result is that we have only a sea of individual Hindus, hardly ever seeing themselves as appendages of a Hindu organism. They have the deceptive appearance of a ‘majority group’ in India.

For decades now this rabble of individuals has been mistaken to be a group. Nothing could be further from the truth, except on rare occasions such as the Ram Janmabhoomi Movement. A Hindu (of the ‘secular’ strain) knows no fury like a fellow Hindu who demurs with his pretensions of omniscience. A Hindu (of the devout strain) knows no irritant like an ‘intellectual’ Hindu eager to disavow his Hinduness. A Hindu knows no salt on the wound so abrasive or acid so corrosive as a fellow ‘Hindu’ who mocks or denies his religion-based persecution.

Nor has any other race so elevated a fetish for self-hate and hara-kiri to a museum-grade art form as have the Hindus.

Such being the conjuncture, it is a distant goal that Hindus develop the same intensity of community consciousness as imbues the Jews. Even then, it would be decidedly controversial to view those outside the Hindu pale as ‘enemies.’ What can be done, nevertheless, is to accept at least that Hindus alone can champion the cause of Hindus, and that Hindus need only champion the cause of Hindus and of no others. Entire industries of activism and literature are devoted to others; none to us.

Mercifully, our situation may not be so volatile as the late 1910s, when the cause of Khilafat, which had no bearing on Indian nationalism, unchained the pernicious creature called pan-Islamism which eventually ended up partitioning our sacred geography. But polarizing ourselves for others does, nevertheless, a disservice to our national fabric.

Hopefully, the dust of passion will settle, and sanity prevail.

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text.