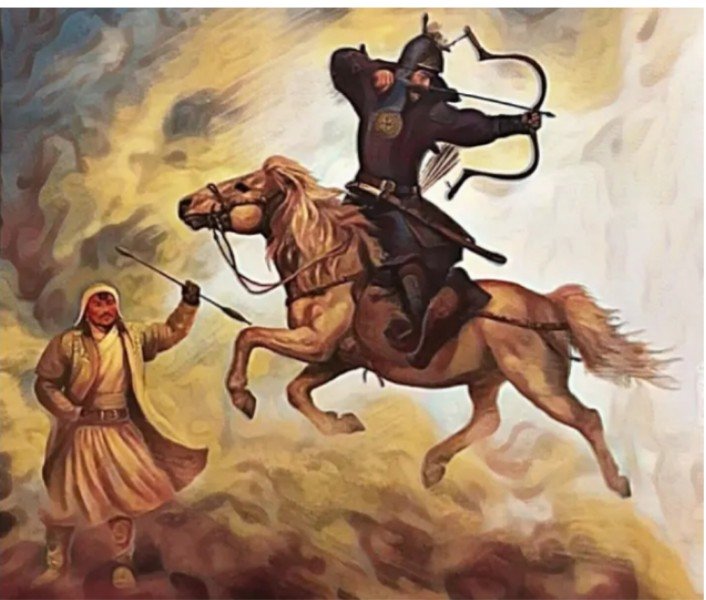

The mystery of Genghis Khan’s remains

‘Do not let my death be known. Do not weep or lament in any way, so that the enemy shall not know anything about it. But when the ruler of the Tanguts and the population leave the city at the appointed hour, annihilate them all.’

These were the words of the mighty Genghis Khan somewhere close to his death period, according to a version of biography of Genghis Khan Persian historian Rashid al-Din. The death of Khan is shrouded in a mystery. Additionally, everything around the time when Khan found out death is inevitable, he made sure that all movements, all strategies were revealed only to a few close aides. John Man writes in his book ‘The Mongol Empire’ in great detail. According to Man, it was during August 1227 when Genghis had just occupied Western Jin, which he planned as the base from which he saw to completely conquer North China and extend his empire. Around that time the emperor of Western Xia was on his way to surrender. It was at this crucial moment that Genghis caught typhus. Other sources claim that he fell from his horse and the injuries did not heal properly, becoming the cause of his death. According to most Historians, Genghis was about 100 kilometres south, in Qing Shui. It was immediately decided by him that although his illness was serious, but no hint of its seriousness must leak out. So, on the first day of the last week of his life, Genghis was rushed in a closed cart into a valley in the Liupan Shan where it was possible to guarantee secrecy and perhaps remedies could have been found from the forest’s medicinal plants. However, those medicines did not work. His entourage faced the possibility whereby if Li Xian, the emperor of Western Xia heard that Genghis was dying or dead, he would have turned around and form alliances with his former allies in China to save his own kingdom. If that had happened, the former allies could have joined forces against their common enemy, the Mongols, and killed Genghis’s grand strategy for future conquest. Therefore it was decided that no hint of the truth must leak out so that the Western Xia emperor would become the first of his treacherous people to die.

As per the plan, the Xia emperor arrived, was puzzled when Genghis Khan met him from behind a curtain, laid out his offerings neatly. Some historians wonder whether Genghis was even present behind the curtain at this time, or whether he was already dead. Following this ritual by the Xia emperor, he was killed in the typical custom which required that no blood was shed when it came to eliminating rulers. According to Man, the killing of rulers, like the killing of all nobles, demanded the observance of a ritual long recognized by the Mongols. No blood was to be shed as the person was either be trampled upon or strangulated.

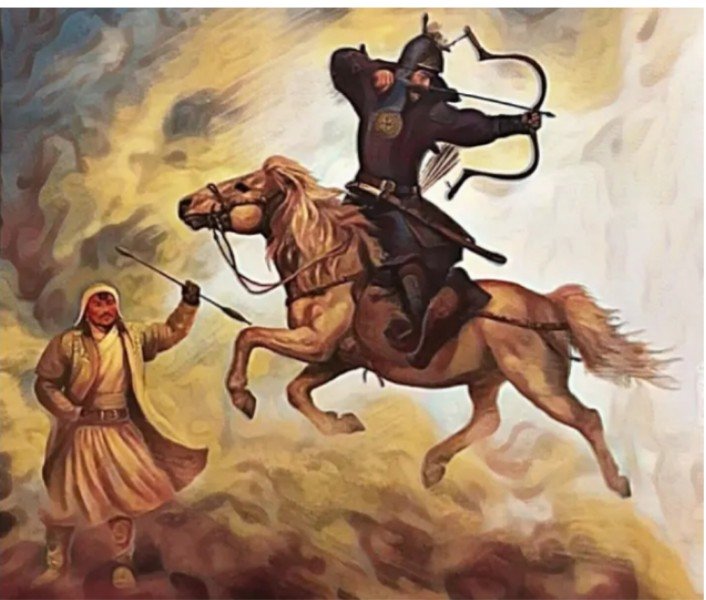

Coming back to the matter of Genghis’s death, there are many speculations on the matter on how and when he died. As for his bodily remains, there is no grave but the Mongols who revere and celebrate Genghis have a firm belief on how he was killed and what happened to his dead body.

The tradition in Mongolia claims that the corpse was brought back across the Gobi to the homeland of the Mongols and buried in a secret grave. However, he died during high summer time and it would not have been possible to cover 1600 kilometers on a cart with his body hidden in less than 3 weeks. The Mongols knew nothing of mummification. It is there fore a safer assumption to hold that the details about his remains are omitted from the Chinese historical documentation to hide the knowledge of the burial site from all but the innermost circles. Arabic writer Rashid al-Din has remarked that while the entoruage of funeral was heading towards Gobi: ‘On the way they killed every living being they met.’ Marco Polo’s claim is indirect: ‘when Mangou Kaan [Mönkhe Khan, Genghis’s grandson] died, more than 20,000 persons, who chanced to meet the body on its way, were slain’.

In his book, Man has shared his reluctance to accept these accounts and has instead talked about Friar William of Rubruck, who was at Mönkhe’s court in Karakorum in 1253–5. and who has not mentioned this story in the detailed account of his trip. Nor does Juvaini, who was in Karakorum at the same time as Friar William. Man holds that both Rashid and Marco wrote the accounts fifty years after the event. Rashid did not speak Mongolian and was dependent on help from his master, Ghazan (ruled 1295–1304, five generations removed from Genghis). And Marco did not attribute the murders specifically to Genghis’s cortège, only to ‘any emperor’ and specifically to Mönkhe (who died fourteen years before Marco arrived in China; he did not see any imperial funeral). Man asserts that what he wrote of them was hearsay. He further goes on to say that the Mongols could have killed the Chinese and Tanguts but could not possibly have killed their own people. He insists that the best way to preserve secrecy is to travel fast, travel small and not advertise the fact that you have something to hide.

In conclusion, Man mentions two possibilities for where the remains of Genghis Khan could be. The first one is that the funeral cortège took another route which would head almost due north for three days across Kherlen to old Avraga, near where, there is a burial ground, and it is possible that Genghis lies there. The second possibility he mentions is that a more likely spot would be up ahead, upriver, in the Khentii, in a place for which many are still looking.

Reference: “The Mongol Empire – Genghis Khan, his heirs and the founding of Modern China” by John Man

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text.