Understanding the history of the “Hindoo” in America is the first step to fighting back.

ask yourself whether academics would so casually sponsor a conference on "Dismantling Wahabbism" or "Dismantling the CCP."

ask yourself whether academics would so casually sponsor a conference on "Dismantling Wahabbism" or "Dismantling the CCP."

Thread by Vishal Ganesan.

The Dismantling Hindutva Conference isn’t actually about dismantling hindutva b/c dismantling any political movement requires understanding, and based on the speakers invited, it’s abundantly clear that understanding isn’t the goal.

Additionally, the fact that 40 universities (allegedly) including some of the world’s best would sponsor this conference cuts against the premise that hindutva is a “global” movement at all, even if the fight against it is. If you doubt this point, ask yourself whether academics would so casually sponsor a conference on “Dismantling Wahabbism” or “Dismantling the CCP.” The answer is no, because there would be actual consequences. The BJP/RSS lack the $ & competence to play this game. Moreover, not only does speaking out against “hindutva” not pose a professional risk for an academic, if anything it’s a good move.

So what is this actually about, and why are departments from some of America’s best universities supporting it? I see this conference as another chapter in a long history of contestation about how the “hindoo” is represented in America. One of the notable patterns I’ve noticed in my research for #HindooHistory is the frequency with which Hindoos are described as “fanatic,” not because they are doing anything particularly extreme, but simply for doing normal “hindoo” things. Here’s an illustration of an ascetic from an 1893 piece. In the caption he is described as “A Hindoo Fanatic”

Here, in a piece about the “Sacred Cesspools of India,” a Hindu pilgrim jumping into a river is described as a “Hindu Fanatic”.

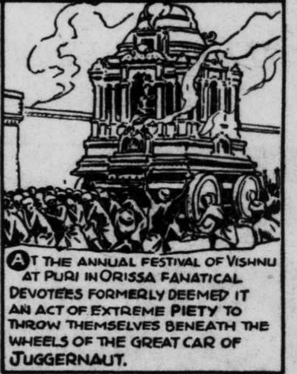

Rehashing a well-established trope, attendees of the Jaggnath Yatra (i.e. Juggernaut) are described as “fanatical”.

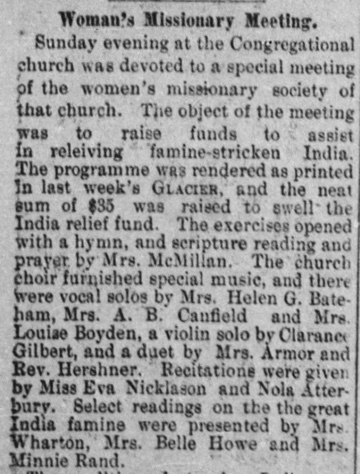

In this article, which recounts the proceedings from a “Women’s Missionary Meeting,” the Hindoo religion as a whole is described as “fanatical”.

This is just a small sample, but there are examples abound. So what’s going on? From the late 18th century when Hindu texts first started reaching American shores, the religion of the Hindoos was understood as quintessentially irrational vis a vis Protestant Christianity There is a deeper intellectual background that you can read about in the substack post linked here, but the basic idea was that for early American scholars of comparative religion, the “truth” of a religious belief was a test of its validity hindoohistory.substack.com/p/the-hindoo-a…

The “Hindoo” and the Enlightenment View of Religion In a letter written to Thomas Jefferson in 1814, John Adams— expressing his fear of the effects of factionalized electioneering on American political institutions— writes “Election is the grand Brama,…https://hindoohistory.substack.com/p/the-hindoo-and-the-enlightenmentThis way of thinking about religion naturally privileged Protestant Christianity, which was accepted as the evolutionary zenith of religious thought. The Hindoo religion, OTOH, came to represent the opposite. Whereas Protestants sought a divine truth consonant with rationality, the Hindoo was mired in superstition and idolatry; Protestantism embodied progression, while the Hindoo religion was one of declension and gradual degradation. Indeed, it wasn’t just that the Hindoo religion was backward, it was the Hindoo himself. The passage below is taken from Two Years in India or Some Missionary Lessons, And How They Were Learned. by Rev. Geo W. Isham, published in 1893.

We’re told that “the pagans are, in all things, ‘too religious.’ The fundamental order of things with them is false and illogical, and has been through the thousands of years of their history”. Isham continues: “Through all the ages they have exercised themselves to believe lies and contradictions, and from his earliest efforts the pagan child is trained to thus pervert his mind. And these perversions are religiously sacred.” To come back to the “fanatic” point, b/c Hindoo belief was based on superstition and untruth, it was inherently “fanatical,” i.e. irrational. And b/c it was beyond rational justification, the Hindoo’s faith had to be due to some perversion of the mind (or priestly trickery). This was a deep prejudice in American culture. So deep that even those sympathetic to the Hindoo in American society made their case by emphasizing the “rational” aspects of the tradition (e.g. characterizing Vedanta as a sort of Oriental Unitarianism).

Indeed, even when Emerson and Thoreau rebutted missionary polemics against the Hindoo, their critique focused on missionary hypocrisy rather than disputing the underlying argument (e.g. Christianity as practiced is full of superstition and idolatry as well). So here we see the emergence of the “good hindoo” that stood in contrast to the hindoo depicted in the popular press. The “good hindoo” offered the transcendental wisdom of oriental mysticism, but without the heathen baggage. But the “good hindoo” far from being static, was a dynamic representation that shifted with larger societal currents. In the early 20th century as Vivekananda’s Vedanta Society was gaining popularity, even the protestantized hindoo came under attack. In her essay on “The Heathen Invasion of America” Mabel Potter Daggett traces the origins of the invasion to the world parliament of religions in 1893, and argues that the Vedanta was a gateway to full-on heathenism, idolatry and all This contestation continues today, though in a different form.

Although critics insist that “hindutiva is not hinduism,” in practice this distinction is extremely nebulous, and the label of “hindutva” is applied liberally to anyone who does not toe the ideological line.Today’s “fanatic,” like the “hindoo fanatic” of the early 19th century, is one whose “common sense” remains situated in their tradition, rather than the ideas of the elite liberal academy. It is no surprise, then, that “hindutva” as a movement is deliberately kept obscure. That’s the point. “Hindutva” for the purposes of this new mission can’t be a legible political ideology, because a projection of the long-standing American paranoia about “hindoo” influence. Its contours are sufficiently broad to apply to virtually anyone who speaks out against academic distortions of Hinduism, and if you are an academic then there is a particular pressure to ensure that you remain a “good hindoo” lest your career prospects be threatened. America is a remarkably open society, but the paranoia about hindoo influence is a real one that goes back centuries.

Like Daggett (referenced above) and Katherine Mayo, she embodies a deep cultural tendency. As long as events like this conference are examined without context, the response will continue to be inadequate or mis-targeted. Understanding the history of the “Hindoo” in America is the first step to fighting back.

———–

Author: /end Addendum: If you are interested in this topic, follow me @HIndooHistory and subscribe to the substack hindoohistory.substack.com (it’s free)

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text.