Afghanistan: “Historical Splendid Cultural Country Burned by Cult of Pakistan’s ISI Sponsored Terrorism” (Part 1 of 3)

Archaeological evidence indicates that urban civilization began in the region occupied by modern Afghanistan between 3000 and 2000 B.C.

The first historical documents date from the early part of the Iranian Achaemenian Dynasty, which controlled the region from 550 B.C. until 331 B.C. Between 330 and 327 B.C., Emperor Alexander defeated the Achaemenian emperor Darius III and subdued local resistance in the territory that is now Afghanistan. Alexander’s successors, the Seleucids, continued to infuse the region with Greek cultural influence. Then, Hellenic culture took root in the region, with the Greek language, script, and iconography in frequent use, including on the coins of Greco-Bactrian rulers[1].

Somewhere in the mid-third century B.C., nomadic Kushans established an empire that became a cultural and commercial center.

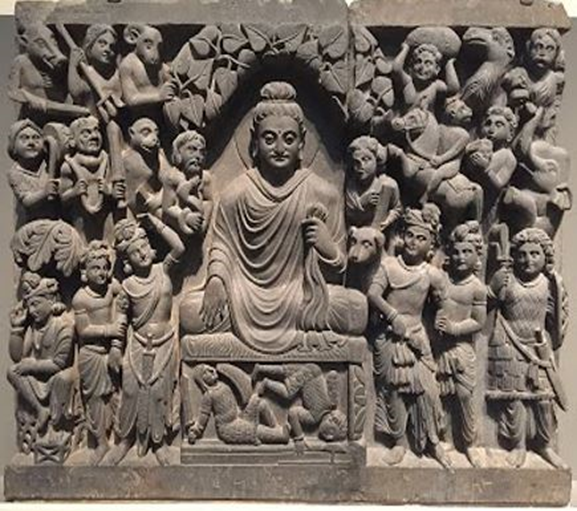

Shortly thereafter, the great Indian dynasty known as the Mauryas wrestled with the Greek successors of Macedonia Emperor Alexander, for control over Afghanistan in the late 4th century. And gained control of southern Afghanistan, bringing with it Buddhism, “Religion of Peace”. From the end of the Kushan Empire in the third century A.D. until the seventh century, the region was fragmented and under the general protection of the Iranian Sassanian Empire.

This is evident from the coins of Agathocles (who ruled in the 2nd century BCE) mingled Greek and South Asian imagery and writing, placing Buddhist and Hindu figures on the front of many coins. This fusion of cultures spread southeast to Gandhara, the historic region that straddles modern-day Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Archaeologists in the 1960s found one of the king’s rock edicts written in Greek – a nod to the remaining Greek communities in the region – near Kandahar in the south of Afghanistan as well as a multilingual rock inscription in Greek and Aramaic. The Ashoka Greek edict was taken to the National Museum of Afghanistan in Kabul from where it was stolen in the turmoil of the early 1990s.

The ancient city of Balkh in what is now northern Afghanistan sat along with one of the routes of the Silk Road. Balkh was one of the great trading posts of the region and served as a political and religious center for millennia. According to some sources, it was from Balkh that the prophet Zoroaster first preached the religion that would become Zoroastrianism, the official faith of several Persian dynasties[2].

Bactria – the wider region around Balkh – came under Persian rule as a satrapy, or province, of the Achaemenid empire and then centuries later under the rule of the Parthian and Sassanian dynasties. In between, it was among the conquests of Emperor Alexander, who left an indelible mark on the territory and its culture.

The famous Indian Proverb is based on the city of Balkh.

“jo sukh chajju de chubare, na balkh na bukhare”. Which means “East or West, Home is best”.

Afghanistan was once part of the trade route between South Asia and Central Asia. Buddhist texts would journey through the region along the Silk Road to the great translation centers of the Taklamakan desert before eventually reaching China and spreading the religion there.

Buddhist foundations and monasteries flourished, resulting in the construction of the gargantuan Bamiyan Buddhas in the 6th century. The puritanical Taliban destroyed these Buddhas in 2001, a desecration that sparked outrage around the world.

Islam arrived in the region in the 7th century after the swift Arab advance through the remnants of the Persian Sassanian empire at the Battle of Qadisiya in 637. Arab Muslims began a 100-year process of conquering the Afghan tribes and introducing Islam.

A succession of Muslim dynasties grappled over the region, especially after rich deposits of silver were discovered in the Hindu Kush in the 9th and 10th centuries and caused something of a frenzied “silver rush” akin to the gold rush in the American West. These silver dirhams above were minted under the Samanid dynasty, whose patronage of the arts saw the development of Islamic and Persian-language culture –often described as “Persianate” culture” –that would spread as far as South Asia.

By the tenth century, the rule of the Arab Abbasid Dynasty and its successor in Central Asia, the Samanid dynasty, had crumbled. The Ghaznavid dynasty, an offshoot of the Samanids, then became the first great Islamic dynasty to rule Afghanistan.

Mongol forces of Genghis Khan have invaded most of Central Asia by 1220. Afghanistan remained fragmented until the 1380s when Timur consolidated and expanded the existing Mongol Empire. Timur’s descendants ruled Afghanistan until the early sixteenth century.

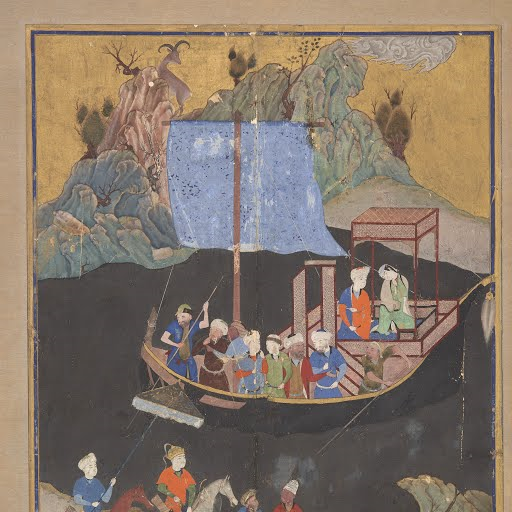

After being razed to the ground by Genghis Khan’s Mongol army in the 13th century, it recovered to enjoy a golden period of political and cultural prominence under the Timurid dynasty until the 16th century. The city of Herat in western Afghanistan was a major trading center, famous for its intellectuals, poets, artisans, and painters. The poet Rumi described Herat as “the pearl of Khorasan” and “the pleasantest of cities.”

In the painting from a Timurid-era manuscript composed in Herat, a king’s female attendant is abducted by her lover. The scene comes from the famous Khamsa or “quintet” of the Indian poet Amir Khusraw Dilhavi, a testament to the sweeping ties that bound Herat to the wider Persianate world.

Herat remains a bustling city, but it has suffered in recent times like the rest of the country.

In the early sixteenth Century, the modern-day Afghanistan region fell under a new empire, the Mughals of northern India, who for the next two centuries contested Afghan territory with the Iranian Safavi Dynasty. With the death of the great Safavi leader Nadir Shah in 1747, indigenous Pashtuns, who became known as the Durrani, began a period of at least nominal rule in Afghanistan that lasted until 1978.

The first Durrani ruler, Ahmad Shah, known as the founder of the Afghan nation, united the Pashtun tribes and by 1760 built an empire extending to Delhi and the Arabian Sea.

The empire fragmented after Ahmad Shah’s death in 1772, but in 1826 Dost Mohammad, the leader of the Pashtun Muhammadzai tribe, restored order again.

Dost Mohammad ruled at the beginning of the Great Game, a century-long contest for domination of Central Asia and Afghanistan between Russia, which was expanding to the south, and Britain, which was intent on protecting India. During this period, Afghan rulers were able to maintain virtual independence, although some compromises were necessary. In the First Anglo-Afghan War (1839–42), the British deposed Dost Mohammad, but they abandoned their Afghan garrisons in 1842. In the following decades, Russian forces approached the northern border of Afghanistan. In 1878 the British invaded and held most of Afghanistan in the Second Anglo-Afghan War.

In 1880 Abdur Rahman, a Durrani began a 21-year reign that saw the balancing of British and Russian interests, the consolidation of the Afghan tribes, and the reorganization of civil administration into what is considered the modern Afghan state.

During the war period, the British secured the Durand Line (1893), dividing Afghanistan from British colonial territory to the southeast and sowing the seeds of future tensions over the division of the Pashtun tribes.

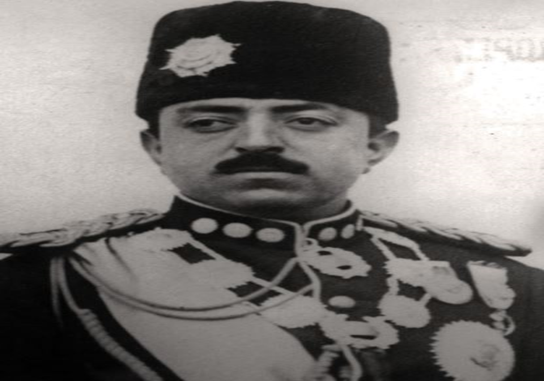

Abdur Rahman’s son Habibullah (ruled 1901–19) continued his father’s administrative reforms and maintained Afghanistan’s neutrality in World War I.

In 1919 Afghanistan signed the Treaty of Rawalpindi, which ended the Third Anglo-Afghan War and marks Afghanistan’s official date of independence. In the interwar period, Afghanistan again was a balancing point between two world powers; Habibullah’s son Amanullah (ruled 1919–29) skillfully manipulated the new British-Soviet rivalry and established relations with major countries. Amanullah introduced his country’s first constitution in 1923. However, resistance to his domestic reform program forced his abdication in 1929. In 1933 Amanullah’s nephew Mohammad Zahir Shah, the last king of Afghanistan, began a 40-year reign.

After World War II, in which Afghanistan remained neutral, the long-standing division of the Pashtun tribes caused tension with the neighboring state of Pakistan, founded on the other side of the Durand Line in 1948. In response, Afghanistan shifted its foreign policy toward the Soviet Union. The prime ministership of the king’s cousin Mohammad Daoud (1953–63) was cautiously reformist, modernizing and centralizing the government while strengthening ties with the Soviet Union.

Pakistan who was an ally of the USA during the Cold war era started impregnating jihadi values in Afghanistan and as a result of which in 1963 Zahir Shah dismissed Daoud because of his anti-Pakistani policy and thus the downfall of Afghanistan’s economy started.

[1] History of Afghanistan – Nations Online Project

[2] The Incredible History of Afghanistan — Google Arts & Culture

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text.