Forgotten anecdote of Dr Birendra nath Mazumder: a doctor, allied soldier and a victim of racism

Life in New Britain, off the north-east coast of New Guinea, during the Second World War, was grueling – and agonizingly so for Allied prisoners of war (PoWs) interned by the Japanese. “There on the ground I lay, shivering, helpless,” recalled one soldier of his captivity after he had caught malaria in July 1943, describing in visceral detail the torrential rain, wet clothes, and mosquitoes. “The thin cotton blanket given to me was inadequate to protect me from the cold, I waited for the sun to warm me. I would shiver like a leaf. Then, seized by fever, my body would turn as hot as fire – I would become unconscious, then awake only to find myself perspiring. There was not a soul who could give [me] a sip or even cold water.”

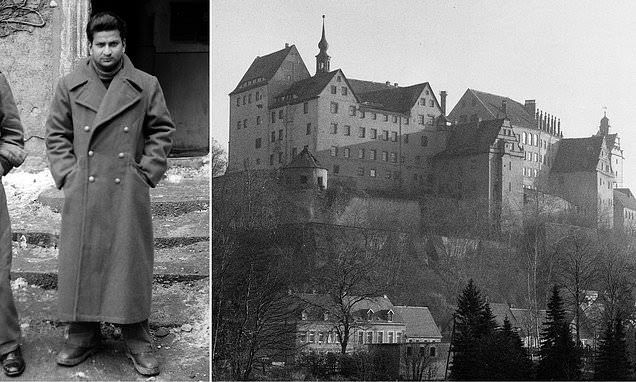

On the other side of the world, a doctor – also a captured Allied soldier, brought to Colditz Castle at the heart of Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich in 1943 – experienced a similar sense of acute loneliness. After hearing the sound of the key turning as the door was closed behind him, the doctor asked the sentry in German where he was; putting fingers to his ears, the sentry remained silent, leaving the prisoner in complete darkness in his cell. Confined within the forbidding walls of the castle, this was as much psychological incarceration as physical imprisonment. In September 1941, a fresh batch of prisoners arrived to join the British contingent of officers at Colditz castle, the formidable fortress in Nazi Germany where troublesome prisoners of war were locked up.

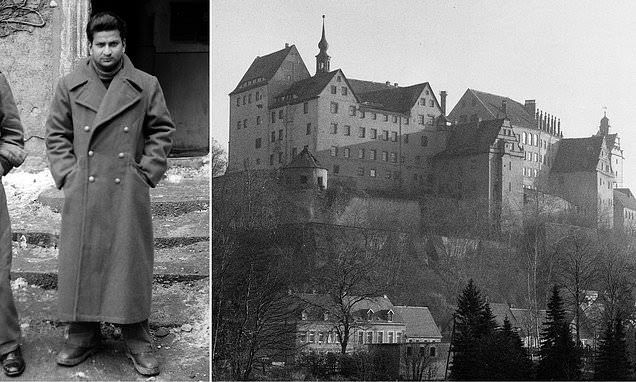

One, in particular, stood out among all the white faces. He was Indian. Birendranath Mazumdar was a surgeon and a very good one. Born into the high noon of the British Raj, well educated, with elegant manners and fastidious tastes, he spoke English with a refined accent – as well as Bengali, Hindi, Urdu, French, and German. The story of a brave British Indian officer who escaped from the Nazis and made his way to Britain during World War II, despite all odds have been forgotten.

Birendranath Mazumdar was an Indian-born doctor whose appearance not only made him stand out in wartime France but led him to be ostracised by his fellow British officers at the high-security German prison camp at Colditz, an account of the story published by The Times said. It narrates how he leaped from a moving train, crawled through barbed wire fences, and made a 560-mile journey through enemy territory before eventually reaching the UK where he died in 1996.

He had been educated at elite schools modeled on the English system and brought up to observe a code of honor that was Victorian British in tone: duty, loyalty, morality, and sincerity.

Mazumdar sounded and behaved like an Englishman, but to many Englishmen, he did not look like one. Among Indians, he was a figure of respect, even grandeur, an educated, high-caste Hindu from a rich family; but to the majority of white men, he was just another Indian.

He had left India in 1931 for London, intent on becoming a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons. ‘To succeed, you have to be ten percent better than the others,’ he was warned. He was proud, funny, ambitious, occasionally obstreperous, solemn, and conflicted: a product of two distinct, entwined, and increasingly incompatible cultures. Most notably, as a follower of Mahatma Gandhi and radical Subhas Chandra Bose, he believed in Indian independence.

Yet despite his opposition to the British Empire, when war was declared in 1939 he joined up, volunteering for the Royal Army Medical Corps. Mazumdar joined the Royal Army Medical Corps and was posted to the French base of Etaples. Despatched to France with the rank of captain, he was the only non-white officer in the corps and the only Indian officer in the British Army. He was told to lead a convoy of ambulances out of Etaples to Boulogne in 1940, according to a Rediff article. German troops surrounded them on the way and Mazumdar, who surrendered, was held, prisoner. He was captured by the Germans in the fall of France and quickly made himself a thorn in their side.

When a German officer ordered him to have his head shaved before delousing, he refused, saying that in Hindu culture ‘you only shave your head when your father or mother dies. He was dragged off to the barber and then to a solitary cell.

He kept up his defiance for his fellow prisoners, complaining of inadequate medical supplies and insufficient food – behavior that mystified the Germans.

‘You are an Indian,’ they told him. ‘Why should you care if a few Tommies die?’ The Times story says Mazumdar was the only Indian at Colditz, the imposing castle used by the Nazis to house prisoners considered troublesome or an escape risk.

But Mazumdar was persistent, and as his relations with the Germans worsened, he was shuttled from one PoW camp to another, more than a dozen in all – a difficult customer, and an anomaly.

His attentive medical care and willingness to confront the Germans ought to have endeared him to his fellow inmates, but he was always a creature apart, treated with suspicion, and occasionally outright discrimination.

The other prisoners called him ‘Jumbo’, after a Victorian elephant that was once the star attraction at London Zoo. It was a nickname he detested but could not shift. The prisoners may have assumed that Jumbo was an Indian elephant, and attached the name to the sole Indian prisoner. In fact, Jumbo was an African elephant, but in the eyes of certain white people, elephants, like Indians, were all the same. Nicknamed “Jumbo”, by British officers, he was offered no help in his wish to escape. They thought he couldn’t escape because of his foreign appearance and treated his request with derision. They told him, “You? Escaping from here? With your brown skin?”

To the Germans, though, this man treated by his own side as an outcast represented an opportunity. They set about trying to persuade him to switch sides. He was asked to make a radio broadcast encouraging Indians to join a new military unit to fight the British and hasten the end of the Raj. He resisted repeated Nazi attempts to persuade him to switch to their side and fight against the British in Burma.

He refused all their overtures, and as a result, was sent to Colditz. From the start, he was treated differently, allocated a top bunk at the back of the upper attic in the British quarters, which meant that if he needed to urinate in the night, he woke room-mates by clattering in clogs across the wooden floor, and endured a flurry of curses.

He naturally gravitated towards the only other person of color in the castle, a half-Indonesian officer in the Dutch East Indies army. That alliance of outsiders only seemed to compound his unpopularity.

But his major problem was that word had spread that, though the Indian doctor may be anti-German, he was also anti-Raj.

This raised suspicions that he would be tempted to make a common cause with his captors. There were murmurings that he was a spy, and fellow prisoners avoided him. The high-caste Indian had become untouchable. The most serious consequence of this was that he was excluded from the camp’s primary topic of conversation: escape.

When he brought up the subject with the Senior British Officer (SBO), saying he would like to be considered in escape attempts, the suggestion was greeted with derision. ‘With your brown skin?’ he was told. It was difficult enough to evade capture in Germany with a white face, said the SBO, let alone a brown one. The Germans kept nagging away, trying to turn him. One day, he was summoned to a meeting at Colditz with another Indian, dressed in the field grey uniform of the German Wehrmacht and wearing the leaping tiger badge of the Indian National Congress.

As a train took him and other Indian prisoners to western France in February 1943, he forced the carriage window open and leapt out. He hiked for more than 150 miles towards the Pyrenees but was arrested near Toulouse, according to the account in The Times. By June 1943, he reached a central French camp at Chartres, where he and another prisoner named Dariao Singh planned a further escape. Singh bored through a two-foot thick wall and then forced open a window that was sealed shut with tin sheets.

They crawled across 500 yards of open ground in the next three hours and cut through three barbed wire fences before scaling an 18-foot tall gate. The duo then reached the Swiss border, traveling at night and crossing three rivers with help from French civilians.

After Mazumdar’s return to Britain in 1944, the intelligence agency MI5 questioned him as he had been introduced to Indian freedom fighter Subhas Chandra Bose who sought German help to liberate India from the British. He was a member of the Tiger Legion, a 1,000-strong unit of Indian soldiers enlisted by Chandra Bose, the Indian nationalist who had now thrown his hand in with the Nazis on the grounds that any enemy of the British was a friend of his.

Having been smuggled out of India by the Germans, Chandra Bose was now in Berlin and the visitor brought an invitation to Mazumdar to meet him there.

Word quickly spread through Colditz that Mazumdar was being taken to meet the Indian quisling raising an army to fight the British in the Far East.

Most assumed that the Indian doctor had already switched sides, confirming their suspicions of disloyalty. ‘We never expected to see him again,’ said one. On the morning of his departure, Mazumdar was cleaning his teeth in the washrooms when someone remarked loudly: ‘That bloody Mazumdar is a spy, he’s going to Berlin.’

Mazumdar turned in a cold fury. ‘I give you five minutes to withdraw this accusation,’ he said. When the 6ft 2 inches Guardsman refused, they squared up and 5ft 7 inches Mazumdar floored his accuser with a right hook and jumped on top of him.

Joan Williams, who married Mazumdar in 1950, told The Times, “Biren never thought of himself as British, but he never felt like an outsider here, as he did inside Colditz.”

“Biren was my life, in a sense”, Williams, 96, said of her late husband as she was thankful that his story was being told in the forthcoming book Colditz: Prisoners of the Castle. It is based on Mazumdar’s account in a tape recording held by the Imperial War Museum and in declassified files of MI5.

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text.