The BJP-RSS’s Foray into Assam’s Tea-Garden Vote-Bank – Himanta Biswa Sarma’s Master-Stroke Comes Right On Time

For the first time after India’s Independence, the Government of Assam, under the initiative of Education Minister Dr. Himanta Biswa Sarma, is going to set up 119 model high schools in different tea gardens of the state. An amount of Rs. 1.19 crore has also been earmarked for the project and the construction work is expected to be completed before the next academic session. E.g. in Doomdooma LAC area of Upper Assam, the foundation stones of six such high schools to be set up at Tara, Dohedaam, Tipuk, Bordubi, Koomsong, and Diamoolie tea estates were laid by the MP of Lakhimpur Lok Sabha constitutency Pradan Baruah on November 1, 2020.

It is a revolutionary step which no previous governments in the state had bothered to undertake since India’s Independence. Pessimists crying foul over the future of these schools that they would soon meet their own terrible fate just like other government schools, seem to have lost sight of the fact that at least a beginning has been made by the current ruling dispensation in the state in regions that have always remained deprived in terms of basic infrastructure. These schools would become functional from the next academic session onwards. In the first phase, six classrooms along with the headmaster’s office room, teachers’ common room, toilets, boundary wall, entrance road to the school, etc. will be constructed by spending an amount of Rs. 1,19,75,000/ under the aegis of the PWD.

This is indeed a welcome move that is aimed at ensuring enhanced access to education of the socio-economically and financially backward tea garden community of the state. They constitute an extremely crucial vote-bank and any political party desiring to control the reins of power can ignore it only at its own peril.

It may be recalled here that the discovery of tea in Assam during the mid-19th century had resulted in populating the state with vanavasis who were brought in from the Chhotanagpur region to work as labourers in the large British-owned tea estates. They had embraced Assam as their homeland since a long time back, and assimilated themselves with the Assamese culture and ethos. However, due to the short-term and petty electoral policies of the previous governments in the state, they continue to remain a marginalised lot. As a result, they have not been able to reap the benefits of the various development schemes and programmes of the government at par with the other communities of the state.

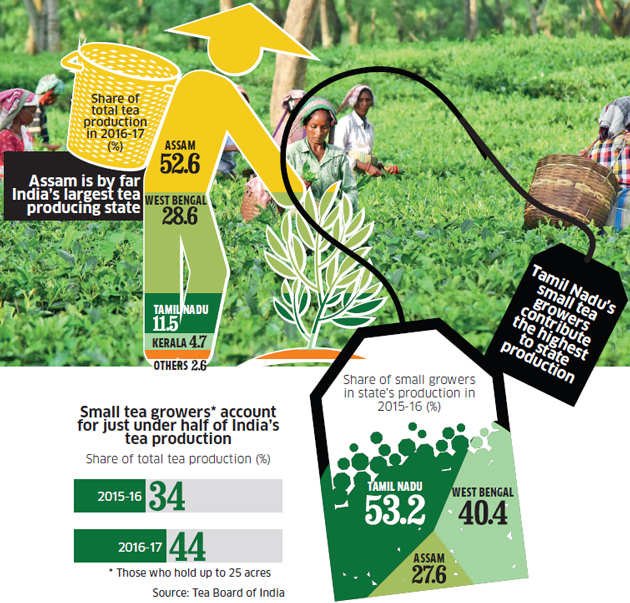

There are roughly around 800 tea gardens spread across seven different districts of Upper Assam – Jorhat, Golaghat, Sibsagar, Dibrugarh, Tinsukia, Lakhimpur, and Dhemaji. A ride through the highway from Dibrugarh to Makum in Tinsukia and beyond, is reminiscent of a very powerful aroma of freshly-plucked tea-leaves. No wonder, a large majority of the people both in India and different parts of the world still wake up to a cup of simmering hot Assam tea. However, one of the most important factors acting as a serious obstacle in addressing the development concerns of these areas is their inadequate access to healthcare facilities and education. Without addressing these two issues through concrete development plans, it is naïve to expect any significant change in the socio-economic status of the people residing in these areas.

One of the strongest ministers in the state with a clout that matches none other than CM Sarbananda Sonowal, Himanta Biswa Sarma’s step-by-step ascendancy in the political power hierarchy of Assam is something which has always kept the politics of Assam ever-fascinating. His recent decision to sanction funds for the construction of 119 model high schools in the tea garden areas of Assam, with the required amenities such as modern classrooms, teachers’ restrooms, entrance gates, separate toilets for teachers and students, etc. is a laudable one. It comes at a crucial time when the state is gearing up for the upcoming legislative assembly elections scheduled for April-May 2021 and the opposition Congress-Left-AIUDF combine again seems to have peddled its feet into the muddied waters of the same old secular/communal divide!

Well, a bit of a recap of the historical and socio-political dynamics that still continues to influence the voting pattern of the tea garden communities in the state. The manual labour required at the various tea estates in Assam is the main source of employment for this section of people. Almost four generations of these people have been living in the state uptil now, but unfortunately, only a very few families have been able to free themselves from the clutches of poverty and move on to other professions. A major chunk of this population has been left abandoned, and leaders remember their existence only when the time of electioneering approaches. The feeling of living in a city, eating in posh restaurants, buying expensive clothes for their children and families are fantasies for them even today! Hardly have they had an experience of life outside these estates. It is the estate managers who are the micro-managers of their physically laborious daily schedules, including the time of their eating and sleeping.

Demographically speaking, the tea garden workers, ex-workers and their families account for upto 31 lakh people, or nearly 17% of the state’s population. Hence, the BJP’s entire strategy of clinching a clean sweep of the votes in Upper Assam depends much on the support it receives from the tea tribes. It is because the tea workers are in a position to influence the outcome of as many as 60 assembly constituencies and 5 parliamentary constituencies – Kailabor, Mangaldoi, Dibrugarh, Lakhimpur, and Jorhat. Hence, in the run-up to the 2016 state legislative assembly elections, the BJP, aided by the RSS, invested a substantial amount of time and effort to make further consolidations in the electoral progress that it had registered in the tea estates during the 2014 Lok Sabha elections. The Congress Party had little time in hand to turn the tide in its favour.

E.g. for the first time in the television history of Assam, a TV commercial was broadcasted in the Santhali dialect which is the predominant language spoken by the tea garden communities. It highlighted the pathetic state of affairs suffered by their previous four to five generations, right from the time when they first migrated to Assam till the present day. A century ago, they were plucking tea leaves for ten hours a day, and even after a century later, they were doing the same for a similar number of hours each day. The advertisement was a stark reminder of the criminal neglect of the successive Congress regimes in the state to make substantial improvements in the lives of the tea garden workers, who now wanted to find their voice as free citizens.

A well-constructed image of PM Narendra Modi who was a tea-seller himself enhanced the credibility and mass appeal of the advertisement further, resulting in significant electoral gains for the BJP. It was in this context that the rally of PM Modi at Moran in Upper Assam – a constituency having a sizeable chunk of the population belonging to the tea garden community – on February 5, 2016, was strategically aimed at making a serious dent in the tea garden vote bank of the Congress Party. The mere mention by PM Modi in his speech of his past profession of a chai-wallah was enough to help him establish a close connect with the coterie of the tea workers’ community. Most of them being migrants from the present-day region of Jharkhand and Chhotanagpur, they easily identified themselves with a leader who did not belong to Delhi and was seen as an ‘outsider’ for a long time even after he had gained access to the corridors of power through a democratic exercise.

In Modi, the tea garden community of Assam saw a ray of hope and change from their wretched conditions. It was from this time onwards that the migrant labourers working in the tea plantations and primarily settled in Upper Assam, broke away from the fold of the Congress. Perhaps to never return back again!

Very soon, the Congress Party realised the fact that the blowback it had already faced in its traditional tea garden vote bank was an irreversible political change, and the only way through which it could make an impact was by exploiting the complex relationship between the tea garden workers and the estate managers. As already mentioned, the latter has always been infamous for exercising a disproportionate influence over the labourers; and, the relationship that had come to be developed between the managers of the privately-owned tea estates and the Congress regimes was kind of a two-way understanding for mutual benefit. Right from dictating the choice of labour union of the workers to which political party they should vote for, the estate managers had usurped the basic rights of free speech and expression of the tea garden communities over the years.

In order to ensure that the tea workers vote en-masse for a particular candidate of a particular political party, these managers deploy estate security to escort the workers and their families to the polling station on the day of the polls.

In this way, the estate managers were quite successful in controlling the political narrative of the region that naturally swung in favour of the Congress Party. This nexus was nourished by the most influential labour union active in the region, i.e. the Assam Chah Mazdoor Sangh (ACMS), chiefly because of its affiliation with the Indian National trade Union Congress (INTUC), its parent body, and also because of its open political affiliation with the Congress Party. Till 2014, the ACMS had exercised almost a kind of virtual monopoly over the issues of organisation and lobbying of the tea garden labourers in favour of the Congress in Upper Assam.

Through years of hard work among the tea garden labourers which has remained deliberately under-reported in the popular media houses, the Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh (BMS) – an RSS-affiliated labour union – has been able to check the monopoly of the Congress-led ACMS to a large extent. Had it not been for the BMS, the BJP would not have been able to script a glorious victory in the 2016 legislative assembly elections. It was undoubtedly a tough journey for the BMS to establish for itself a strong foothold in the tea garden areas of Upper Assam by not only building an entirely new tea workers’ union from the ground, but also helping to garner enough political support for the same with time. Nevertheless, it has been successful in carving out a fresh brand of politics in the region by constantly reminding the tea workers about their betrayed past in which both the labour unions and the incumbent governments failed to fulfil their promises of providing them with basic living amenities under the Plantation Labour Act of 1951.

In this way, the tea garden workers have been made aware of the opportunities that they were deliberately made to lose under the Congress regimes vis-à-vis the labourers in BJP-ruled states. This awakening was accompanied by PM Modi’s aggressive co-option of the sentiments of the tea workers, which eventually led to a crucial electoral mandate in favour of the BJP.

Hence, the recent decision to set up 119 model high schools in the tea garden areas of Assam is a master-stroke by the Assam BJP to further consolidate its earlier electoral gains in these regions. It has also started scholarship and financial assistance schemes for the students of these communities who aspire for higher studies, besides the setting up of coaching centres for the youth who wish to appear in different competitive examinations, and providing scooters and bicycles to girl students. The party has also assured of fielding more candidates from among the tea community aspirants in the 2021 legislative assembly elections. The Congress seems to be finding itself in a tough position with respect to regaining its lost ground in the tea belt areas of the state, considered to be its traditional bastion.

However, certain important issues such as according Scheduled Tribe (ST) status to the tea garden communities as promised in the BJP’s election manifesto of 2014, daily wage hike, allotment of land to each landless family of these communities, providing employment to the unemployed tea garden youth, among others await a well thought-out resolution. Moreover, the revival of the 150 sick tea gardens of Assam in both the Brahmaputra Valley (around 130) and the Barak Valley (around 20), besides the 15 Assam Tea Corporation tea gardens and the fate of around 1.5 lakh workers in these tea gardens still hangs in balance. In the years ahead, the BJP needs to work upon these issues with the right political will. Only then can real poriborton (change) come about in the lives of a community of a people who have always been left to the margins, their voices stifled and basic freedoms denied.

References:

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text.