Hindus Must Shun Their false identity

Can you imagine the agony of living under a false identity — an identity of transgenerational shame and ignominy? Such agony is part and parcel of the living experience of a Hindu. When the real identity is revealed, one feels liberated, elated.

The question of identity and how we relate to the rest of the world and beyond is an exercise explored by social scientists, anthropologists, and spiritual scholars alike. In modern and contemporary epistemology identity is considered either in terms of “linkages of social structure” or “internal process of self-verification” (Sheldon Stryker and Peter J Burke, 2000, The Past, Present, and Future of an Identity Theory, in Social Psychology Quarterly)

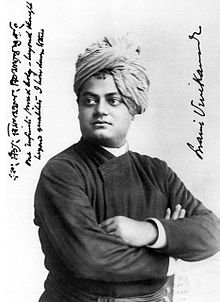

‘Who am I?’, however, is a question related to identity and the eternal journey of the human race. It is a journey that makes Adi Shanka leave the comfort of his Kerala house at a tender age of eight. From Gautam, the Buddha, to Swami Vivekananda — there are numerous similar examples in the Indic Tradition as ‘Self’-exploration, in this tradition, is the ultimate goal of human existence.

But what happens when people realize that they have been robbed of their identity, or worse, they have been forced into a wrong identity?

It was the 2014 Maulana Azad Memorial Lecture (November 11) organized by the Indian Council of Historical Research (ICHR), an autonomous body under the aegis of the Ministry of Human Resource Development of the Government of India. SN Balagangadhara (Balu), a professor of Comparative Science of Cultures at the Ghent University in Belgium, while delivering the Lecture, was recounting his 40-year journey of academic research. Very soon in his research, he discovered that there were many problems in his understanding of European as well as Indian history. Most of the knowledge about India that makes it to Indian textbooks is a description of India by foreign traders, travelers, and the Christian Missionaries, he noted. He further said that the description of India these textbooks gave based on those accounts “was not the India I lived in.”

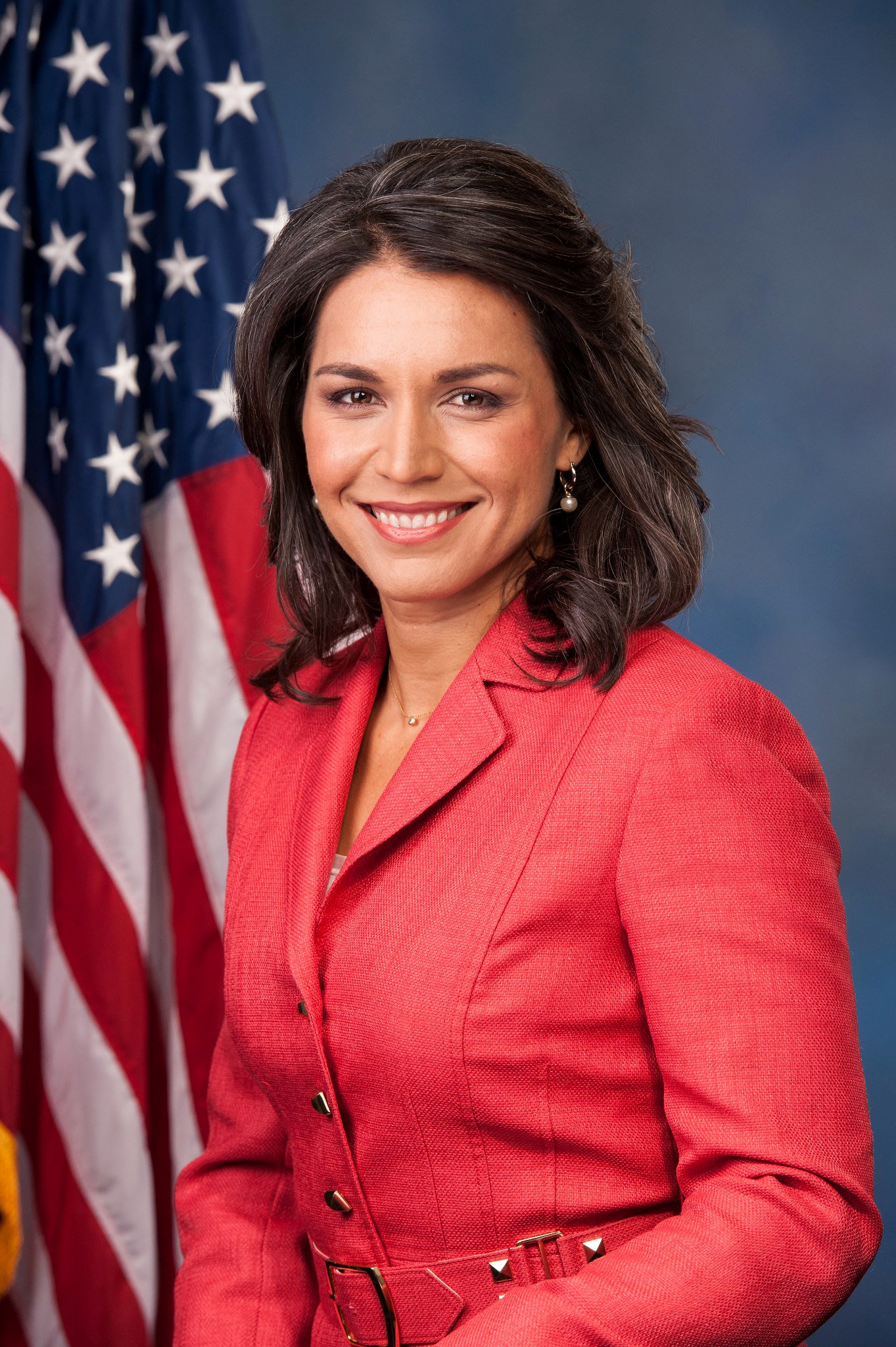

Not too long ago, it was during the primaries of the 2020 US Presidential election that Tulsi Gabbard faced a similar situation. During one of the National Public Radio (NPR) interviews, the interviewer referred to ISKCON as ‘cult’.

The pertinent question to ask here is – why is it difficult to navigate Indic/Hindu identity? In the case of Indic/Hindu identity, it is often the case that others defining it takes precedence. This phenomenon, what Arvind Sharma, Birks Professor of Comparative Religion at McGill University, calls an “outsider to outsider” view in the academic world, has reached a level where a Hindu scholar’s views have not only been marginalized but they have also been rendered useless. In the academic circles, a Wendy Doniger or a Sheldon Pollock has more validity than the Hindu thinkers such as Swami Vivekananda, Sri Aurobindo, or Ramana Maharshi.

In the last 200 years or so, the foreigners and the Marxists have dominated the study of India, its culture, traditions, texts, religions, etc. The emergence of Indology as a field of study of India can be traced back to neo-Protestant theology and their debates over scriptures as well as its anti-clerical prejudices. These prejudices over time, but consciously, were applied to the study of Indian texts where one can easily trace the antecedent of anti-Brahmanism.

These foreign Indologists believed, according to Vishwa Adluri, that “Indians lacked access to the “true” meaning of their texts… for Indians never developed scientific critical thinking”. Adluri, a Professor of Religion and Philosophy at Hunter College, along with Joydeep Bagchee, has exposed the problems of the so-called ‘scientific method’ of the German Indologists in their acclaimed book The Nay Science: A History of German Indology.

The University College Chapel, Oxford monument of Sir William Jones is a prime example of this prejudice. The monument shows Sir Jones comfortably sitting on a chair and writing something on a desk. The monument also shows three Indians squatting in front of him. The inscription underneath reads: “He formed a digest of Hindu and Mohammedan Laws”.

Post-independence Marxists, on the other hand, consciously hid and denied any reference to India’s past achievements. They also picked up from where the colonialists and missionaries left in demonizing almost each and every facets of Indian society.

The question of Indic identity gets further complicated due to some of the markers used for this process. These markers have, over time, changed our own perception of ourselves. Religion is one such marker that is fundamentally flawed and inadequate when applied to describing Indic faiths. The predominant Abrahamic notion of religion is utterly incapable of describing and nuancing the Indic ‘religions’. Similarly Dharma, the modern Indic equivalent used for ‘religion’, comes nowhere to describing a ‘religion’.

In terms of history writing, the indigenous Itihasa has been replaced by the “study” of the past. Balu calls modern Indian history writing “an old knee-jerk reaction to the Protestant critique of Indian culture and tradition” and a great knowledge-based indigenous culture has infamously been reduced to ‘caste, cow, and curry’.

As Indians, we are constantly reminded of how horrible our society has been, how badly we have treated our women, and even burnt them alive on the pyre as ‘Sati’. We are constantly hounded by the accusation that we have the world’s worst discriminatory ‘caste system’. We, polytheists, pagans, and kafirs, are ridiculed for not only worshipping ‘idols’ but how we also worship thousands of ‘gods and goddesses’, how we cannot take care of our places of worship, so on and so forth. The list is endless.

It won’t be an exaggeration to state that even in the remotest corners of the world people know about India’s tyrannical ‘Brahmanical caste system’ before they learn ‘I’ of ‘India’. Notwithstanding the many prevalent exploitative discriminatory systems around the world such as class, feudalism, communism, racism, slavery, Girmitiya (indentured) labor system, etc., the worst kind of contempt is saved for the ‘caste system’.

Despite the preponderance of academic literature, both in India and in the West, on the topic of the ‘caste system’, there is no consensus among the academicians about “how the caste system came into being and what sustains it”, write authors of the Prakash Shah (Reader in Culture and Law at the Queen Mary University of London, UK, ed.) book Western Foundations of the Caste System. The authors meticulously investigate this issue and come to the conclusion that the foundation of the Indian ‘caste system’ is predicated on the Western, Christian theological notions and historical experiences.

The case of ‘Sati’ can also be explained on similar lines. There has been one ‘Sati’ incident in India in the last 3-4 generations. Yet this issue keeps getting harped on to demonize Hindus and Indians. In her book Sati: Evangelicals, Baptist Missionaries, and the changing colonial discourse Meenakshi Jain (professor of history at Gargi College) emphatically shows that the bogey of ‘Sati’ was a cooked up one at best. The Evangelicals and the various Christian missionaries used a few random incidents to further their own agenda and to justify their own presence as well as justification for colonial rule in India.

It is now time for Hindus to overcome and overthrow their imposed identity and assert own indigenous and Sanatan self-identity.

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text.

1 Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Credible