Iran: Protesters being raped inside jails by Iranian IRGC agents.

Members of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), also known as Sepah-e Psdrn-e Enqelâb-e Eslâm in Persian or Army of Guardian of the Islamic Revolution in English with nicknames like “Sepah” or “Pasdaran,” are continuing to rape detained female protestors on orders from high command in Iran. This was made known by a letter that a hacktivist collective called Edalat-e Ali (Ali’s Justice) published, which detailed the rape of at least two female demonstrators between the ages of 18 and 23. The paper makes it very evident how the brutal suppression apparatus of the Iranian mullah mafia regime conceals rape and sexual assault committed by its personnel.

Sensitive information about Iran’s security forces and prison conditions has been leaked by Edalat-e Ali. In November 2022, the first reports of demonstrators being detained started to surface, and since then, many victims and their families have come forward to talk about what happened to them.

In a letter from Mohammad Shahriari, deputy prosecutor and head of General and Revolutionary Courts, district 27, to Ali Salehi, prosecutor at Tehran General and Revolutionary Courts, dated October 13, 2022, about the arrest and subsequent rape of the two women, Alireza Sadeqi and Alireza Hosseini are two IRGC agents who are mentioned.

20-year-old protester Armita Abbasi was held in detention for several months until being freed on February 7, 2023.

The two ladies get in touch with Tehran’s police station No. 124 and report being detained and subsequently raped by agents on October 3, 2022, as the deputy prosecutor informs his higher in the letter.

Shahriari remarks right away that the allegation from the two ladies was not filed following “coordination with Hefa [the Persian abbreviation for the police intelligence organisation]”.

A person named Alireza Sadeqi, who is allegedly an agent, and his father were detained at their home in Tehran’s Pirouzi Street, where copious quantities of batons, ammunition, bulletproof vests, police radios, handcuffs, IDs for various law enforcement agencies, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, and the judicial system, as well as a stash of cash and drugs, were discovered.

The letter continues by stating that Alireza Hosseini, an IRGC captain in charge of the intelligence division of the Imam Hassan unit, was also detained and transported to a jail run by a police intelligence unit, and that his motorcycle had been discovered in the residence of the “accused [previously] detained.”

It is unclear in the letter exactly how the two agents were located and apprehended.

The letter goes on to describe how they admitted to raping the two ladies, with Sadeqi admitting that they had held the women while on a mission in Sattarkhan Street, in western Tehran, close to a gas station.

Because there were no facilities for the women’s incarceration at the time, superiors commanded them to release the women. It appears that the rape occurred after the accused took the women back to the location where they were picked up.

After admitting to raping the women, Sadeqi claimed that one of them had made the first move during a sexual encounter in the car and that he had performed the “Sigheh,” a secret and verbal temporary marriage contract that is meant to make sex religiously acceptable. According to the letter, he also named his coworkers Alireza Hosseini, Hojjat Keivanlou, and Ali Shahroudi, suggesting that they may have sexually assaulted the other woman.

However, Alireza Hosseini first refused to acknowledge any sexual abuse, claiming that the arrests were done on the grounds that the ladies were demonstrators.

“I spotted Sadeqi conversing to one of the female captives and told him to keep his distance,” he subsequently admitted in a confession to the crime. After a short while, I noticed him stroking [NAME REDACTEDback. ]’s I yelled at him to stop, but he continued to shove the second girl, [NAME REDACTED], in my direction. I shook my head in confusion and pondered what was happening.

He seems to have described how Sadeqi forced the woman to engage in oral sex as he was “standing with the front side of his pants pulled down and was active” in his following evidence.

Hosseini accused the woman of saying, “For God’s sake, let us loose,” while undoing his fly in reference to his own situation.

The deputy prosecutor draws the obvious conclusion that “the defendants merely formed a gang for extortion or kidnapping and did illegal activities” in an obvious effort to downplay the agents’ misbehaviour in the document. Terms like “autonomous detention centres,” “torture of people,” “extortion,” and “widespread interaction with women and girls” stand out in this section of the letter.

The paper, which can be seen in full below, finally shows how the Islamic Republic’s repression apparatus handles situations involving sexual impropriety by agents:

“Considering the problematic nature of the case, the possibility of this information being leaked to social media and its misrepresentation by enemy groups, it is recommended that necessary orders be issued for it to be filed in the ‘Top Secret’ category. Since no complaint has been registered and the defendants have been dismissed, it is advised that the case is gradually closed without any reference to the involved military institutions”.

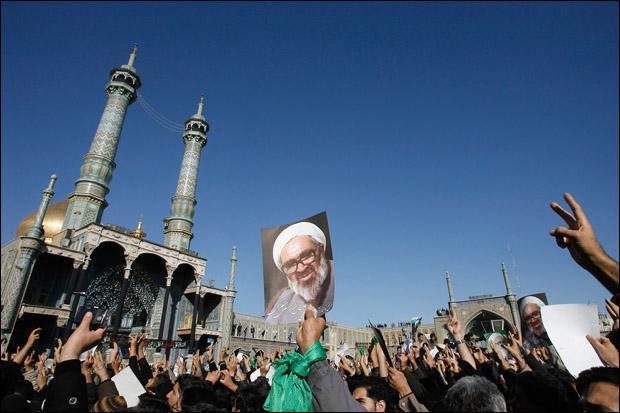

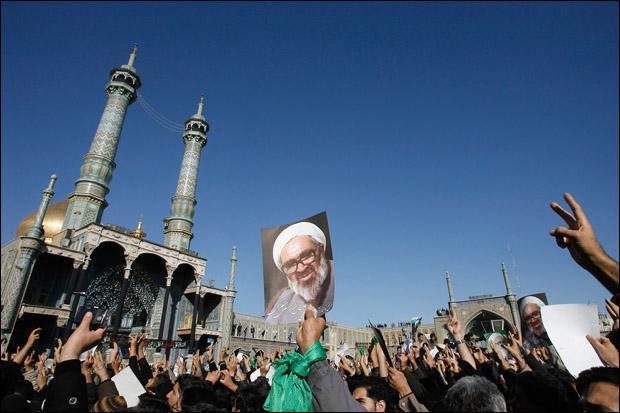

As a result of Mahsa Amini’s death at the hands of the so-called morality police last September, large-scale protests have been taking place in Iran ever since. Several reports have been made public, offering proof of rape and sexual abuse of female protesters from the time of detention to interrogations. Additionally, there have been rumours that security officers shoot women in the face, breasts, and genitalia.

The most recent paper is just one more piece of mounting evidence that the Islamic Republic of Iran’s security personnel, who routinely engage in acts of sexual assault and torture, may carry them out with impunity.

In a story on November 30, 2022, “Iranwire” has reported the horror. The report stated, “… The young woman, identified as Afsaneh, was arrested during recent anti-government protests, the source said. While in prison, she kept yelling at the other inmates she had been repeatedly raped during her interrogation by agents of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps’ (IRGC) intelligence agency.

Afsaneh was transferred to a hospital because of her critical mental and physical condition and was later released, before taking away her own life, according to the voice note.

The torture and sexual abuse Afsaneh, from the city of Bukan, is said to have experienced while in custody has been shared by many women locked up in Iran’s detention facilities.

Fatemeh Davand, a political activist who has been incarcerated at Urmia prison, left Iran last year and is currently living in Turkey. She has spoken to several women recently released from the prison or who remain behind bars there. They said they both witnessed and suffered sexual violence while in detention.”

In a report published on May 31, 2021, Radio Free Europe described how IRGC members and other Iranian security forces, as well as prison staff and guards, sexually harass and abuse female captives.

After the Islamic Republic of Iran was founded in 1979, allegations of rape and other sexual abuse committed by authorities against political detainees started to surface and have persisted to various degrees to this day. However, it should come as no surprise that there is no accurate estimate of the number of inmates who have been raped in Iranian prisons. No statistics or thorough report has ever been prepared that fully captures the scale of sexual assault in Iranian jails.

There are only a few rape victims who are willing to talk about their experiences because of social stigma, political pressure, and official complicity. The Iranian government has tolerated and still condones the rape of detainees by guards and interrogators who use the crime to break the spirits of the victims, humiliate them, quell their protest, coerce them into confessing to crimes, and eventually terrify both the victim and others.

Victims of rape suffer permanent physical, psychological, and social impacts as a result of the trauma they experience. This, naturally, implies that many victims, even years later, are unwilling to openly recognize their experiences. A lot of people haven’t even told their family.

Therefore, it is extremely possible that the few witnesses who have come forward to describe rapes they witnessed and experienced in Iranian jails only make up a small portion of all occurrences given these circumstances.

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text.