The Panoramic Scholarship that Bhārata needs: A Beginning

There has been in existence for some time in Latin American countries, an endeavour to assess the noxious impact that colonialism has had on their cultures, their manners of thought and their ways of life, and amongst the foremost scholars in this field is Professor Walter Mignolo. The school of thought that he subscribes to is the ‘decolonial school’.

It is common in our parlance to speak of ‘postcolonial’ thought, but it suffers the demerit that it contemns the ipseities of the culture and traditions of the colonized peoples. Colonialism must, at its very rudiments, involve the Pavlovian conditioning of the colonized peoples, that the culture of the colonial masters epitomizes reason and progress and is therefore superior to the anachronistic unreason that characterizes the faith and culture of the colonized. Perhaps unconsciously, the postcolonial school accepts the superiority of the colonized, but insists that the colonizing race alone is not the epitome of those virtues which the colonial masters have internalized; that emulating their virtues, the colonized, too, can progress similarly.

The decolonial school defies them both and insists on formulation of progress models that are consistent with the culture of the colonized. It does not care about testing the culture of the colonized against that of the colonial masters.

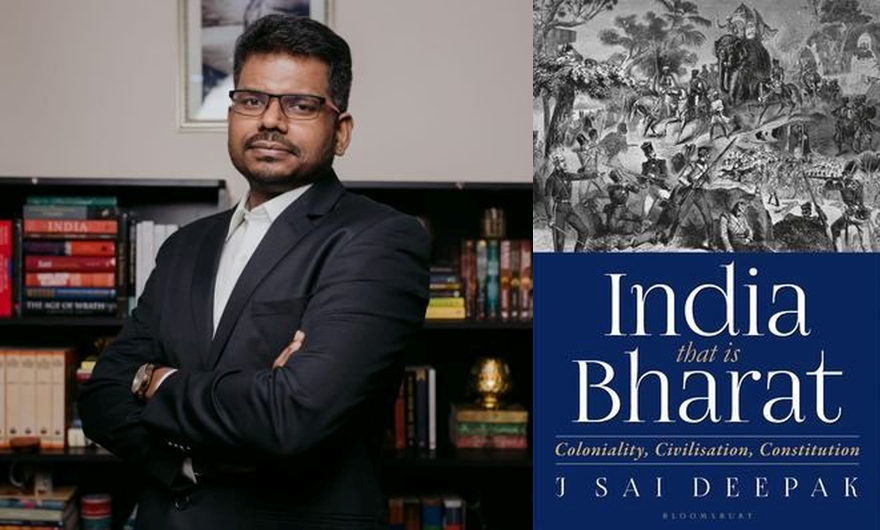

In his book “India: That is Bhārat”, the first in an intended trilogy, J. Sai Deepak advances, and adduces evidence in favour of, the following propositions, amongst others:

This book is highly academic in nature, and a single reading may not suffice to imbibe its contents. J. Sai Deepak, while citing the erudite Walter Mignolo, however, is careful to not render his analysis a facsimile of the assessment that is undertaken in Latin American countries. He explicitizes why, while undertaking a decolonial assessment, India must perforce differ from certain inadequacies that would have characterized the Latin American assessment, had it been applied to India sans such modifications as may conduce to India’s cultural realities.

But this post is an impassioned entreaty to readers, besides that the book be read, that the following talk may be heard. J. Sai Deepak is on a nation-wide tour to promote his book, and the appurtenant conversations are illuminating, to say the least. This particular talk was in the city of Pune, in the amphitheatre of the Ferguson College.

The talk would explain to us many contemporary points of discussion.

Why rumination over the discourse on secularism induces a sense of unease within us: Secularism emerged not independent of Christian theology, but from within Christian theology itself. Citing historical literature, J. Sai Deepak demonstrates how secularism is in fact a far more potent weapon to further the aims of Christian proselytization in unsuspecting countries, than the overt conjurations by missionaries. More on this may also be read in S.N. Balagangadhara’s book, “What Does it Mean to be an Indian?”

Our emulation of Western models of development shall fail: J. Sai Deepak clarifies that he is not adversarial towards industrialization. But he is certainly at unease should we, in the quest for progress, disregard respect for Nature (Prakriti) that is innate to Dharma. The reason behind keeping tribals away from civilization was not out of oppressive and discriminatory proclivities on part of city and village denizens, but a sense of respect for their way of life, for they had ‘cracked the code’ of harmonious existence with Nature.

It is a canorous slogan but an intellectually subpar platitude, that ‘all religions are equal’: The beginning of every culture and its knowledge is its ontology, which is a branch of metaphysics which deals with the nature of being and reality (the relationship between individual consciousness and the Supreme Consciousness). It progresses to epistemology, which is the progress of ontology to knowledge systems; it morphs into science so that metaphysics may be understood better. Subsequently, all of it is rendered comprehensible to the common masses by means of theology. The contempt towards our culture has explicit roots in Christian and Islamic theologies, which has also been demonstrated at length. This is not to insist that every human born into these religious fraternities is an enemy of the Hindu civilization, for that would be a procrustean understanding. Stating so is the mere cognizance of the fact that the existence of such inimical theory has the potential to spawn its practitioners.

One cannot divorce identity from development: One might have often witnessed amongst such of the English-speaking youngsters as are encharmed by the platitudinous views of postcolonial Indian thought, a certain disillusionment with India as it is. Some amongst them have developed a healthy respect for China, which by their reckoning is sailing smoothly on the seas of progress. “It is building air purifiers while we fight on grounds of religion”, one such boy had said in a discussion that I recall.

As I said, the talk is quite illuminating.

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text.