Venereal Disease and the Prostitution Policy of the British Raj

The first known references to syphilis and its treatment in India are found in the Bhavaprakasa, a mid-sixteenth-century text, written by Bhavamisra, an ayurvedic physician at Benares. At that time, and for a long time subsequently, syphilis was known in India as firanga roga or firangi roga, which identified it with the firangis (“Franks” or foreigners). Whatever the origins of syphilis elsewhere, in India, it is likely the disease was introduced from Europe by the Portuguese in the early sixteenth century.

In many of the British principalities in 19th century India, venereal disease among British troops was a quickly becoming a critical issue. The average annual admission of British troops to hospitals for venereal infections, predominantly syphilis and gonorrhoea, was over 200 per 1000; by 1895 this reached a whopping rate of over 500 per 1000. A viceroy writing to the secretary of state for India, acknowledged that “the strength of the British Army in India as a fighting machine has been much impaired by these diseases”.

The likely explanation for this seemed obvious – the majority of British soldiers were young, under-occupied and bored, and hence sought prostitutes, a frequent source of infection. Yet, among Indian soldiers, the reported incidence of venereal disease was much lower; in 1866, for example, the rates of infection for British and Indian troops were 218 and 54 per 1000 respectively.

Indigenous Indian troops consistently demonstrated far lower rates of venereal admission than the Europeans, and their “immunity” was a cause of some resentment.

The viciousness of syphilis seen on the more “civilized” constitution of the English thus became a crucial element in the mythology of superiority, with much medical energy expended on explaining this statistical disparity. The doctors did their best to explain the differences away with half-baked reasonings.

It was suggested that native troops slyly concealed their condition or resorted to “quacks” for indigenous remedies, or that they had possibly become partially immune through frequent exposure (we know for a fact that there is no decreased syphilis risk with repeated syphilis episodes or reinfections). Nobody would entertain the idea that Indian soldiers might just be less sexually promiscuous than the British.

The Indian Lancet (a medical journal) went a step further in denying the superior restraint of local men:

“The point made so much of, that the sepoys are more chaste, possess more self-control as regards sexual intercourse is not true. Anyone who has been any time in India, and has been observant, must have noticed crowds of sepoys visiting native prostitutes. It may possibly be found on investigation that the reason they suffer less from venereal disease than European soldiers is this: they have acquired immunity, having suffered from hereditary syphilis in youth.”

Indian Lancet, April 1, 1897, p. 1.

The principal medical officer in India blamed the combination of “a warm climate and a country of lax native morals” for offering severe temptations to young men.

A memorandum issued by the British on the perils of Sexually transmitted diseases warned soldiers of the infective contamination lurking in local women also proclaimed the assumption that diseases caught in the tropics were more ravaging than those acquired in the “gentler” climates of northern Europe. It was commonplace for venereal disease contracted in the tropics to be represented as a worse and more savage entity, affecting the “refined white constitution” with greater severity.

(We know now that this is scientifically inaccurate: lack or improper of treatment of syphilis allows it to progress to the deforming stage)

The justification for the wildly different experiences of local and foreign troops in India all point to the critical need to reinforce European superiority over Indians, whether through asserting that tropical disease was “more virulent” than European, or that Indian morals were “less developed” than Victorian.

In a 1905 memorandum, Lord Kitchener, Commander-in-chief of the Indian Army, warned his troops:

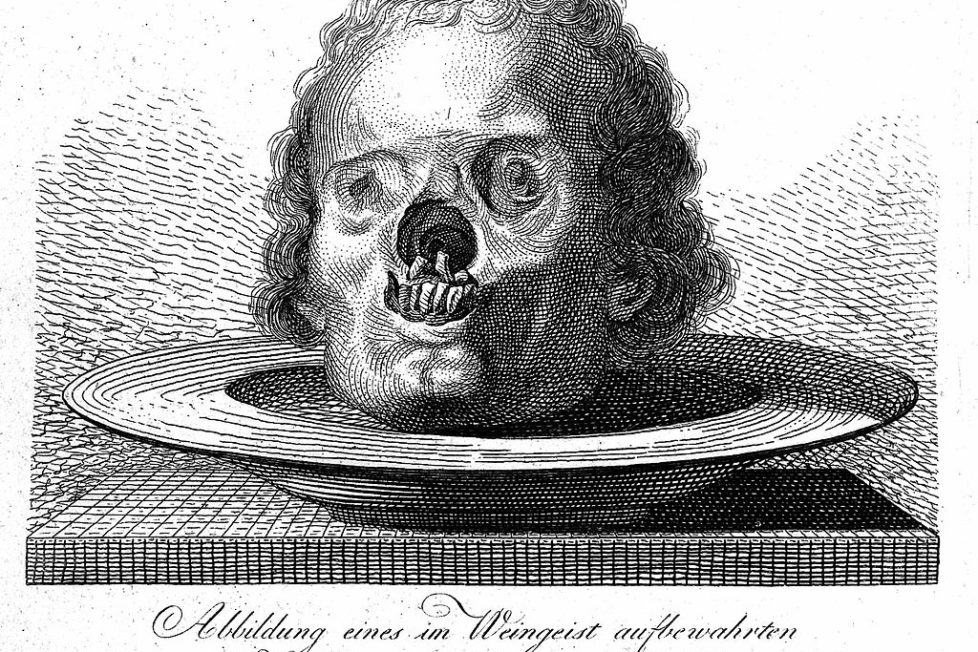

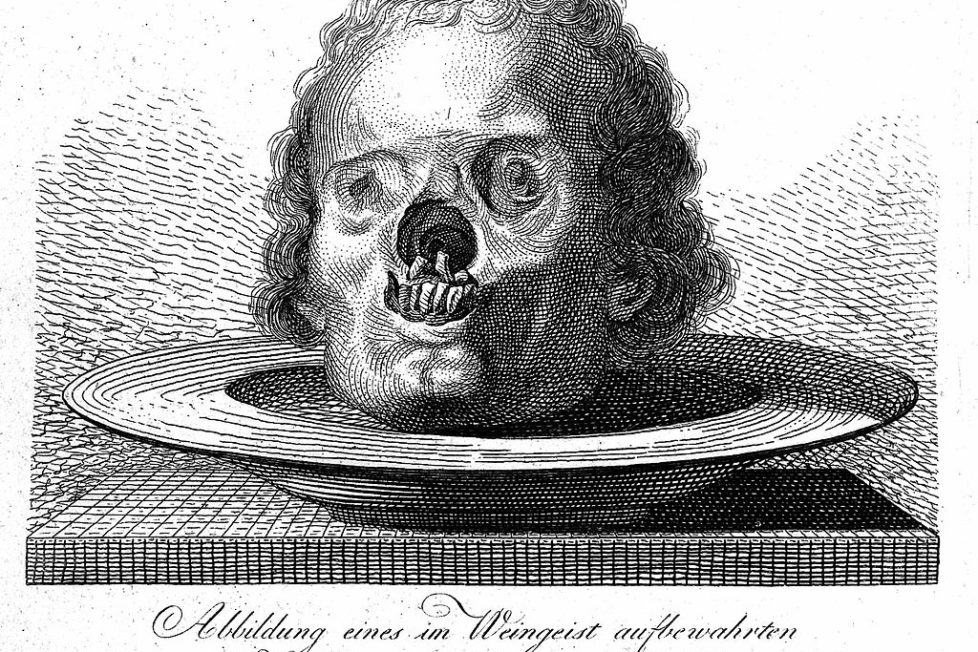

“Syphilis contracted by Europeans from Asiatic women is much more severe than that contracted in England. It assumes a horrible, loathsome and often fatal form through which in time, as years pass on the sufferer finds his hair falling off, his skin and the flesh of his body rot, and are eaten away by slow, cankerous and stinking ulcerations; his nose first falls in at the bridge and then rots and falls off; his sight gradually fails and he eventually becomes blind; his voice, first becomes husky and then fades to a hoarse whisper as his throat is eaten away by fetid ulcerations which cause his breath to stink.”

This passage is illustrative, not just for its dramatic description of the worst-case scenario, issued to intimidate soldiers contemplating the dalliances with prostitutes of the dangers of becoming contaminated by physically overt disease, but because it creates a fearful image of the ‘syphilization’ of the British race, through degeneration by venereal disease.

In post-Mutiny India, sexually transmitted diseases among British soldiers and the legislative measures enacted to decrease their incidence extended into a lengthy controversy, both in British and Indian discourse, to which Lord Kitchener’s military policies in the early 20th century were central.

Military authorities did not solely rely upon mercury (injections of mercuric chloride or calomel or ‘grey oil’) in order to deal with STDs within the army, since other nouveau drugs such as salvarsan and neo-salvarsan** (arsenic compounds discovered in 1909) weren’t discovered until later.

The incidence of sexual diseases among troops continue to rise despite regular inspection and warnings issued against prostitution, as an effective treatment for syphilis had not yet been discovered and a “cure” at this stage was, in most cases, simply a temporary suppression of symptoms.

Military authorities had long accepted that an outlet for their soldiers’ sexual energy was essential.

The provision of women—registered, inspected, and available—was seen as a method of exercising medical and disciplinary control over their troops, and as a cheaper alternative to a substantial increase in the number of soldiers’ wives allowed. It was far preferred over the alternative – increase in masturbation, seeking prostitutes who were potential sources of infection, or homosexuality*, which was particularly dreaded.

*Although there’s more to it, a note on homosexuality: The Raj was convinced that without sexual contact with women, the British army would verily become “Sodom and Gomorrah”. The imposition of section 377 starting in 1860 that punished sodomy, buggery, and bestiality as offenses wasn’t sufficient – reports stated that the military men were a willing market for homosexual acts on young boys, were women not readily available. In 1894 Viceroy Elgin declared that a lack of prostitutes it would lead to more deplorable “oriental” and unnatural evils. The threat of homosexuality, not only as a vice but also as potential damage to the reputation of the empire – was cited to justify the making available of prostitutes to the armed forces.

In effect, the British authorities were conspiring at setting up a system of licensed brothels (resembling the French maisons tolérées) and issuing license cards for prostitutes (who could be arrested if caught without one) solely for sexually servicing their troops: a system of brothels that had been specifically rejected back home in Britian (through the Social Purity Campaign launched in 1869, a movement rooted in “Christian ideals” that rallied against prostitution). Yet in India, the same Christian morality didn’t seem to apply, since the seeming requirement for prostitution outweighed any moral hesitations.

When “Christian England” took control of “heathen India,” about a hundred plots of land called Cantonments were sectioned off across the country for the residence of the British soldiers/officers, and provisions were made such that soldiers didn’t need to venture out of the cantonment area for any necessities, including those of the flesh. The Cantonments Act of 1864 and the Indian Contagious Diseases Act of 1868 jointly organized the sex trade within military cantonments and enabled supervision, registration, and inspection of prostitute women in major Indian cities and seaports. It was a system devised for furnishing sensual indulgence to the British soldier, under the assumption that it would protect him from venereal disease.

Unlike its counterpart in Britain, which, was limited in its jurisdiction to about 18 military districts in the British Isles, the Indian Contagious Diseases Act directly affected the indigenous population not only within a four-mile radius of all one hundred or so cantonment areas, but to most urban areas of cities where the legislation was later extended to apply.

Indian prostitutes were segregated in specially designated enclosures called ‘chaklas’ (brothels) within the cantonments, where there was usually also a lock hospital. Around 12-15 native women were assigned to regiments of about a thousand soldiers, but this number varied according to the requirements and fancies of the Cantonment Magistrate. Apart from women that were already in the flesh trade, a number of women of all castes were often pressured to leave their homes or abandoned or abducted, only to be sold to the cantonment magistrates and forced to move into these chaklas*. A prostitute wishing to take up residence in a chakla had to apply for special permission to be placed on the register of prostitutes maintained by the Cantonment magistrate. She was then sent to the ‘lock hospital’ for genital examination before permission was granted. Henceforth the women were obliged to go periodically (generally once a week or fortnightly) for a genital examination, to ensure their body was free from any trace of disease likely to spread from them to the soldiers. Lock Hospitals and the Cantonment Act that ordained their establishment were attacked by critics in Britain and India for affectively licensing, and thus approving, prostitution and for causing undue harassment modesty of innocent women.

Note * The British argued that all chakla women belonged to the “prostitute class”, that existed before the instatement of their system, but this was simply not true. While many of these chakla girls born into the supposed “prostitute class”, a substantial number were those abandoned by their English fathers – forced to take up residence in brothels established and run by Englishmen. They were born to women of all castes/religions, from brahmins to mohammedans, arabs, and jews; and eventually entered the trade. Outside of the cantonment and traditionally in Indian society, prostitutes were not treated as “outcastes”, rather, they enjoyed a social status, unlike prostitutes in Britain. This distinction was NOT made by British officials who were ultimately responsible for the policy of social segregation of the prostitutes intended for British soldiers. This observation is corroborated in writing in multiple instances, for example, in a note submitted to the British Government by Sir Robert Townsend Farquhar that can be summarized as follows: while in England the prostitute was in an outcaste state, “in India, the condition of the women is far less degraded and their influence in the community is often considerable, so that unwise interference would be frequently resented by the influential classes of people.” In another note issued to the local administrator, the Divisional Commissioner of Kumuon in the Northwest province remarked, ‘the class of women who in India resort to prostitution are mainly composed of persons of the caste “Paturya” or prostitute. This professional caste is not regarded by the natives of the east as dishonorable.” (Oriental and India Office Collections, 1894)

Commander in chief Geoffrey White frequently expressed this widely held knowledge in his official and personal correspondences. “Prostitutes are not looked upon by the natives of India with the contempt which attaches to them in other countries. They are accepted as safeguards to society and are not themselves ashamed of their calling”.

Therefore, while the commonly held assumption was that prostitutes were naturally segregated in Indian cities prior to British intervention, there is ample evidence to suggest that this phenomenon was a direct result of British policy.

Whether this claim was made to disavow responsibility for driving destitute children into prostitution, for the increase in women and child trafficking, and furthermore, the forcible confinement, fortnightly indecent examinations, and institutionalization of Indian women – all for the sexual entertainment of British troops – that is for the reader to judge.

Registered prostitutes in chaklas were called ‘Lal Kurti’ or “queen’s ladies”, and areas of regimental brothels were known as “lal-bazaars”. The chaklas were supervised by superintendents or brothel-keepers/madams called ‘mahaldarnis’*, appointed by the government, who were responsible for the women and also acted as pimps to provide prostitutes for the use of soldiers at the request of commanding officers. Often, official permits were granted to these women go out to procure more women as and when needed. The price of the visits of soldiers to the chakla was fixed by the military at such a low rate that a given soldier would scarcely pass up the opportunity.

*according to one account, mahaldarnis were paid a salary of ten rupees a month from the Government, and in true pimp fashion, also took a share of the girls’ earnings. Mahaldarnis were also furnished with plenty of money from the government with which to acquire slave girls from the bazaar.

A letter of recommendation found in possession of one such mahaldarni reads as follows:

“Ameer has supplied the 2nd Derby Regiment with prostitutes for the past three years, and I recommend her to any other regiment requiring her for a similar capacity.

“S. G. M——,

“Quartermaster 2nd Derby Regiment.

Native men were not allowed near the chakla and an armed guard was present at all times – brothers and husbands who might be bent upon rescuing their female family members who had been enticed or stolen by mahaldarnis, were strictly kept away. No other native men were allowed to touch the girls maintained for white soldiers.

Many cruelties were inflicted upon the women kept in these cantonment brothels by the British. They were often physically abused by soldiers, subjected to cruelties in their drunken states, and at times, even murdered.

If by chance, upon examination, any of these women were found diseased (often, any and all vaginal discharge was mistaken for syphilis, quite unscientifically – hence among women, there may have been an overreporting of the prevalence of syphilis) she was detained in the hospital until “cured”, then given a ticket of license and returned to the chakla. If she didn’t recover enough to be declared “disease free”, she would be let go, her card revoked – hundreds of miles away from home (often these women wouldn’t be accepted into proper society having been a prostitute to foreigners and thus effectively losing her caste status). In case a woman tried to escape from the chakla, or from the Lock Hospital, she was hunted down, apprehended, taken to the Cantonment magistrate, and punished with a fine or imprisonment (Rs.50 and upto 7 years). In many instances, women didn’t even understand why they were being sentenced and imprisoned.

Women were forced into indecent exposure for genital examinations by “doctors”(often with a vaginal speculum, and an inexperienced physician using it: an experience that can be quite painful) under the threat of a penalty or expulsion from the Cantonment (tantamount to starvation); imprisoned in ‘Lock Hospitals’ for several days each month, even when in perfect health; imprisoned for indefinite periods of time if found diseased; expelled if seriously diseased, with their half-British children, to starve, or to spread disease among the natives; and finally, dismissed to starvation when too old to be “sufficiently attractive” to the soldier, if only a fresh victim could be found to take their place; impoverished and receiving a pittance fixed by the military, that kept many of them on the verge of starvation.

“Life in India does not tend to the elevation of British morals, and this not because of the climate, as some contend. The industrial conditions are all against good morals …. Wages are so low in India as to constitute the native the virtual slave of the Anglo-Saxon”, ““If we are expelled, where shall we go” We must leave all our friends, and no one will give us work. It means great hardship; we would starve.” Elizabeth Andrew and Katharine Bushnell

These strict restraints on local women were preferable to regular genital examination of soldiers plus a penalty imposed if found diseased, which would theoretically be easier to enforce, and in practice, a better solution to controlling the outbreak of venereal disease among them. But, citing “reduction of morale” and resultant increased concealment of the disease among troops, they were not subjected to regular checks and hospitalization as the women were.

“Such inspections, performed as they are in barrack-rooms or in sergeant’s rooms, are injurious to the morale of the men, and develop coarseness and injure modesty. . . . Every passer-by, every native cookboy, often women and children, must know what is going on.”

(Fourth Annual Report on the Working of the Lock-Hospitals in the North-Western Provinces and Oudh for the Year 1877 (Allahabad, 1878), p. 97, report for Faizabad)

The squeamishness of soldiers toward genital examination, and the reluctance of higher-ups to admitting the extent of the problem contrasts with their nonchalant attitude when it came to the examination and mistreatment of women. The men’s delicacy and modesty seemed to require protection – a modesty intimately linked to their “refined” European sensibilities. Yet at the root of the issue was the inappropriate Western habits and promiscuity that led soldiers into their diseased state in the first place. Efforts to teach the soldiers self-control had already failed miserably, as evidenced by the “Report of the Army Health Association”, printed at Meerut, in 1892.

The means employed in the attempt to eradicate venereal disease was by licensure of its cause – prostitution, signified extreme moral blindness of the British, to whom native women were sub-human, inferior to “noble” Englishwomen; on top of this, these measures contradicted all scientific logic. Notably, Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell, a British physician, remarked: “We may as well expect to cure typhoid fever whilst allowing sewer gas to permeate the house; or cholera, whilst bad drinking water is being taken, as try to cure venereal disease whilst its cause remains unchecked.”

Provision of prostitutes to soldiers also sought to discourage mistresses or long- term relationships with native women from nearby areas, in an attempt to regulate contact between white British soldiers and Indian women (practically, these illicit sexual relationships still occurred despite the legislations). Military authorities preferred to ensure that a steady supply of “healthy” women were available for temporary hire wherever soldiers were stationed.

The brown Indian prostitute, subservient to the British male, was a paradigm of racial superiority – a critical component to the assertion of European power. In this regard, the presence of few European prostitutes in India was unnerving, and a matter of considerable political gravity to the British; the symbolic servitude of a white woman to the brown man would radically and fatally undermine the basis of colonial rule. The European women were tolerated in the hope that British troops would preferred engaging with them instead of with native Indian women.

The raj had to come to terms with the dismaying possibility that some of these white women might have sex with Indian men – an idea that seemed abhorrent to them. Colonial ideas of sexuality were clearly mapped along racial lines – through prostitution by white women was destabilizing to established colonial supremacy, they always occupied a higher regard than their native counterparts. A sense of anxiety was created around the presence of white prostitutes as they were members of the ruling race yet of the subordinate sex. They were also outside of the influence of the “Victorian and Edwardian” ideals of sexual prudence.

British authorities superficially resolved this conflict, however, by making it publicly known that most European prostitutes working in India were Roman Catholic, Jewish or Mediterranean émigrés from eastern Europe, rather than of Anglo-Saxon western European heritage, and attempts were made to strategically deport those from Britain. To their relief, even the few English women found in the brothels of India were Jews, who were “less white” hence less valuable.

Soldier Frank Richards described the streets of the red-light quarters in British Burma, where one street was exclusively inhabited by Japanese women, another by Europeans. “Somehow I felt thankful when I was told that there was not an English girl amongst them”.

The degradation of white prostitutes plying their wares to natives seemed to be a threat to their imperial station. An effort was thus made to restrict white prostitutes to the port cities and disallow them into Cantonment areas where their racialized cavorting will be plain for all to see. Yet, a troubling trend showed that white prostitutes were moving inwards into the Gangetic heartland of India, settling in places like Lucknow etc. after being ejected from Rawalpindi and Lahore due to their scandalous conduct. European prostitutes often enjoyed far greater agency and freedom to operate than Indian prostitutes.

“.. more from a political than a moral point of view.. The white races are at the present time the dominant and governing races of the world and anything that would lower them in the sight of the subject race should, I think be carefully guarded against, and I do not think that there can be any doubt that the sight of European women prostituting themselves is most damaging to the prestige of white races” Superintendent Shuttleworth, Oriental and India Office Collections, 1917

To prevent the natives from buying the services of European women, the Indian Contagious Diseases Act instituted two classes of brothels occupied by native women: the first class comprised of those reserved for British men and a second class of those reserved for indigenous men.

The 1889 annual report for the Solon venereal hospital, Punjab, reported that the women there were “for the sole use of the troops and were not common to the inhabitants of the station.”

At Kasauli, also in Punjab, “a registered prostitute of the European brothel” was fined two rupees in 1887 “for having sexual intercourse with a native.”

In the early 1880s, the quarter-master general issued a memorandum throughout the country directing that women in first class brothels should “consort with none but Europeans”.

And in the northwestern provinces, the medical officer for the Bareilly district reported in 1885 that registered women, selected because they were the healthiest women, “are supposed to receive the visits of soldiers only”.

In a confidential letter circulated to all officers in both British India and the princely states by the quartermaster general on 20th October 1913, the commander in chief stated that he wished to rid military stations of white prostitutes, on both political and moral grounds by using existing Cantonment Code to shut down their brothels, since white prostitutes were of greater temptation to soldiers, and common natives weren’t able to distinguish western European women from British (any white female was a “mem saheb”).

Even so, here is a quote from a report dated 5 February 1913 written by Helen Wilson, secy. of the British Committee of the International Federation for the evolution of state regulation of voice complaining to the to the Secretary of State to India about ‘white slave trade’ and the freedom with which brothels were established and allowed to run in India:

This passage clearly demonstrates the British governmental concern for white European prostitutes (who were perhaps not over three or four hundred in number in the entire country at any given time, and were in the profession of their own volition) over huge numbers of native Indian women, who willingly or unwillingly resorted to prostitution.

The memoranda issued in demi-official (and sometimes confidential) capacity regarding the acquisition of “attractive” women for prostitution purposes is truly shocking. It was apparently a point of surprise to the military officials that heathen women would not readily flock for containment in the regimental bazaar.

The officer in command of the 2nd Battalion Cheshire Regiment sent the following application to the magistrate of “Umballa” (Ambala district in Haryana) Cantonment:

“Requisition for extra attractive women for regimental bazaar, in accordance with Circular Memorandum 21a: These women’s fares by one-horse conveyances, from Umballa to Solon, will be paid by the Cheshire Regiment on arrival. Please send young and attractive women, as laid down in Quartermaster-General’s Circular, No. 21a.”

The note went on to express a certain displeasure towards the women already being held in the regiment not being “attractive enough”.

A government official employed in the Ambala region at the time related his observations of this prostitution ring run by the British military:

“The commanding officer gave orders to his quartermaster to arrange with the regimental Kutwal [an under-official, native] to take two policemen (without uniform), and go into the villages and take from the homes of these poor people their daughters from fourteen years and older, about twelve or fifteen girls at a time. They were to select the best-looking. Next morning, these were all put in front of the Colonel and Quartermaster. The former made his selection of the number required. They were then presented with a pass or license, and then made over to the old woman in charge of this house of vice under the Government. The women already there, who were examined by the doctor, and found diseased, had their passes taken away from them, and were then removed by the police out of the Cantonment, and these fresh, innocent girls put in their places.”

A few anecdotes of the types of young girls that found themselves held captive in chaklas can be found in The Queen’s Daughters in India by Elizabeth W. Andrew and Katharine C. Bushnell, a couple of missionary women that traveled to India in the early 1890s and wrote an account of the Chakla women, and protested against their treatment, citing it “unchristian”.

Most of these anecdotes are truly tragic and heartbreaking in their chronicling of the desperate and horrifying fate that these girls found themselves in. Here are a couple I’ve chosen randomly, and the rest of this section from the book can be found at the end of this article, along with a link to the book in its entirety.

“A hill girl of respectable family lost her parents and her husband (perhaps only betrothed, yet possibly already married), before ten years of age. A deceitful woman came to comfort her in her grief and unprotected condition, and enticed her to travel with her a month to assuage her grief; sold her to a British official, with whom she lived one year, when he died. She then became a chakla woman. She was only sixteen. She said, “It is a bitter life.”

A high-caste Brahmin girl, not able to understand a word of the language of her captor, found deserted and starving. The captor admitted that she was a perfectly respectable girl, yet she was examined by the surgeon, her name entered on the list of prostitutes, and taken to the Lock Hospital to be prepared for her fate. The poor thing was so grateful to be taken in and fed, and little dreamt of what would be demanded of her in return. We tried in vain to make her understand us, and to warn her of her fate. “

Excerpt from The Queen’s Daughters in India by Elizabeth W. Andrew and Katharine C. Bushnell

The colonial enactments aimed at controlling female prostitution and curbing venereal disease, especially among the British military, differed in important respects from their domestic cousins. Enacted principally in the 1860s, at the same time as the British acts, almost every British colony acquired regulations governing the behavior of prostitute women as a measure against the encroachment of syphilis and gonorrhea. In India, under the two major legislative measures introduced in the mid-1860s, Indian women were subject to tighter control than were British women. An Indian woman could be arrested on suspicion of solicitation even if she was simply walking down the street, if in case she was unregistered and didn’t carry a “card”. She would then be harassed, brought before the Cantonment magistrate, and forced to register as a prostitute and live among the soldiers. Police would often take large bribes, threatening women of this fate.

In India, unlike Britain, military and civil authorities could designate where prostitute women might live and often also the facilities they were required to offer their customers, such as wash-places.

The Indian woman was a dubious moral category when compared to her western counterpart, and her presumed “diseased state” and reluctance to seek treatment was seen as a measure of native recalcitrance to British rule, requiring harsher subjugation.

As venereal disease became more and more a convenient metaphor for savagery or primitiveness, legislation sanctioning and structuring prostitution, in British eyes, was an instrument of the progressive “civilizing” Western mission to tame the devastating effects of tropical sickness.

In 1902, the City of Bombay Police Act was passed, that cited the Indian Contagious Diseases Act in which clause 28 further provided authorities with the specific power to segregate prostitutes and keepers of brothels. It was passed in the wake of Bombay and Madras facing increasing pressure from the center to control the prevalence of venereal disease.

The provisions were similar to those present in prior Bombay and Madras Police Acts– it gave the police Commissioner the power to target the occupants of any building used by prostitutes, forbidding them from residing in or frequenting any location mentioned in a notice. Any person found ‘soliciting for purposes of prostitution and indecent exposure of a person’ could be punished with imprisonment and a fine of upto Rs. 50. This legislation effectively gave way for a functional social segregation – and was put into force as such. Prostitutes began to move away from certain parts of the city and into other areas where marginalized castes generally congregated – leading to an increase in social stigma attached to prostitutes. Much power began to be concentrated in the hands of the police commissioner and his deputies – which was prone to be used as blackmail on the streets.

(Calcutta resisted these efforts to enforce segregation but many other Indian provinces followed suit – for instance, the Eastern Bengal and Assam Disorderly Houses Act II of 1907, and the British Balochistan Bazars Regulation Act V of 1910 allowed magistrates to order the closure of a brothel or a house used for prostitution if it was in the immediate neighborhood of a Cantonment.)

The provision of prostitute women for military men was regarded as politically necessary, pragmatic even. Without available women, it was presumed that soldiers, unable to control their passions in the “tropical heat of the East” would masturbate or turn to either consensual or non-consensual relations with Indian women, or worse- to one another. There was a constant, haunting fear of homosexuality, which would undermine the stature of imperial conquest. In the politics of empire, there was no room for even a hint of the effeminacy assumed to exist among British men. Domination and conquest, masculinity and authority, were interlinked, and critical factors in this power play.

Indian attitudes and tolerance towards prostitution, trafficking of women and girls, and segregated brothels seem to reach a crescendo during the 1910s. Violence against women was increasing – women facing domestic violence who deserted their husbands found themselves trapped in Kolkata’s brothels. Two cases that drew particular public attention and exposed the horrors of the brothel system happened in 1918. One was of a young girl of 14 abducted from a festival and forced into prostitution, and the other was of a corrupt Inspector General that offer protection to a brothel that regularly abducted young girls. Brothels began to be associated with multiple criminal activities such as sodomy, trafficking, and the scandalous sexualization of Indian society, while doing absolutely nothing by way of control of venereal diseases.

The existence of approved and registered women, provided exclusively for the use of troops, is critical to understanding the central placement of sexual politics in the maintenance of the empire. The insistence of colonial authorities on a homogeneous normalization of prostitution was clearly an imposition of Western categories of sexual commerce and behavior upon Indian society.

In Empire and Sexuality: The British Experience by Ronald Hyam (1990), Hyam argues that sex made life in the tropics “bearable” for the British, sexual relations between white men and colonized women was used as an act of racial conciliation rather than that of subjugation. His account takes little cognizance of the relative power exercised by colonizing men and colonized women in such contexts; therefore, it is more probable that prostitution was a marker of colonial servitude imposed upon Indian woman, and by extension, upon the populace at large. British officials likely used sex as a central political mechanism to subdue its subject population as well as to suppress potential unrest from within its own military ranks, more especially after the events of 1857, the history of which became sexualized in the telling so very rapidly (through propaganda in British versions of the event).

This is further evidenced by the fact that historically, imperial conquest, along with looting, pillage, murder, and destruction, has almost always involved some form of sexual conquest, whether that be through rape, or abduction. Hyam spins an almost implausible whitewashed version of the history of sexuality in the empire: one of prostitution being primarily a simple economic supply-demand model rather than one operating in the shadow of imperial, political, and military power.

In this way, the essentialized categories of the East and the West were upheld as crucial racial markers that served to justify the imposition of colonial rule. Prostitution was essentially a central prop of the masculinized colonial rule.

“They print the outrageous falsehoods that represent India as having become a menace to the health of England because of the abolition of brothel slavery in that country. Excuses are made for the shallow-brained sophistry of those who pretend that the compulsory periodical examination of women can be divorced from the moral debasement of women, and as though such compulsory examination were something quite unlike the notorious Contagious Diseases Acts. .”

September, 1897

Elizabeth Andrew and Katharine Bushnell

“I wish that every woman in the United Kingdom could read this little book. It tells the truth, the terrible truth, concerning the treatment of certain Indian women, our fellow-citizens and sisters, by the British Government. I believe if that truth were known throughout the length and breadth of our land, it would become impossible for our rulers to continue to maintain the cruel and wicked Regulations by which these Indian women are enslaved and destroyed.” Josephine E. Butler, a Victorian era social reformer

The two acts of 1864 and 1868 were finally abolished by order of the secretary of state in the late 1880s, as were those effective in Britain and elsewhere in the colonies. In the early 1890s, the controversy nevertheless continued to rage as the antiregulation movement of the moral reform party in Britain scrutinized the cantonment regulations and forced them to abandon the system. It was later once again restored in 1897 after venereal disease among troops had reached an alarming 52%.

Whatever be the case with respect to the incidence of venereal disease, the British used the “health of their troops” as a justification for the imposition of western ideas of commercialization of sex and the vile debasement of respectable women, and imposition of sexual control as a central plank of imperial policy.

“In every Indian cantonment after dark the vicinity of European lines is haunted by women of the lowest and poorest class who, though not prostitutes by profession, are willing prostitute themselves” Oriental and India Office Collections, 1893

In essence, the British rule in India was legitimized by the doctrine of racial superiority and their insistence upon being profiled as the “civilizing” authority, based on maintaining “social distance” between themselves and their Indian subjects.

Touting their misplaced sense of “western morality”, and contrasting themselves from the native “savages” – a policy by which the revered “Devadasi women” of temples were criminalized and outlawed, after classifying them as complicit in an “illegitimate form of prostitution”. (The Devadasi tradition was a long-standing tradition that equipped women with skills in the arts, including poetry, music, dance and literature – and were essentially “married” to the presiding deity of the temple which they served, but were allowed to maintain sexual relationships with rich men that chose to patronize them). When Indian women protested the licensing of prostitution, officials dismissed the protest with the argument that there was no distinction between the indigenous courtesan tradition and the British System of commercial prostitution. The fact that prostitutes were “accepted” in Indian society somehow proved the inferiority of Indian morals, in their view. Their monolithic view of Indian culture and a complete lack of understanding of Indian society led to the imposition of policies that were incompatible and incongruent with the Indian ethos.

Imperialist Britain’s rigid views of morality, rooted in Christian orthodoxy, being superimposed onto a diverse and free Indian society, coupled with the fact that the military occupied a central role in the expansionist agenda of the empire, resulted in their engaging in one of the largest scale human trafficking operations in modern history.

Footnote **The introduction of salvarsan in 1913 aimed to help reduce the levels of venereal disease among British troops stationed in India; but on the flipside were a growing volume of reports of the toxic effects of IV injections of salvarsan due to acute arsenicosis or arsenic poisoning.

From an Indian perspective, there was a certain irony to the use of arsenic as a chemotherapeutic agent, since the use of arsenic by indigenous medicinal preparations had long been criticized as dangerous and unproductive by western physicians and pharmacologists.

Sources

Further reading:

“We will give only a few, in bare outlines, of the many cases not already mentioned:–

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text.