WUHAN VIRUS— WHY DID CHINA BEHAVE THE WAY IT DID?

China is Zhongguo in Mandarin, meaning the Middle Kingdom, or the Central Empire. This centrality is a part of the tradition of China, a civilisational imperative. To understand China, one has to understand its civilisational narrative. Every young officer of the Indian Foreign Service on an assignment to China must do their basic schooling in Confucius and Sun Tzu, yet the lessons of its civilisation are mostly lost on the Indians. It has the following broad characteristics:

1. Unity of the Empire

2. Centrality of China in the scheme of the Universe

3. Emperor as the representative of Heaven on Earth

4. A merit-based bureaucracy (the Mandarins) as the steel frame of the Empire

5. China as the repository of the best in everything, including human endeavour

6. All the best territories are contained within the boundaries of China, the Emperor rules over Tian Xia, or “All Under Heaven”

7. Always keep testing the limits of your power without provoking war ( A Sun Tzu variant)

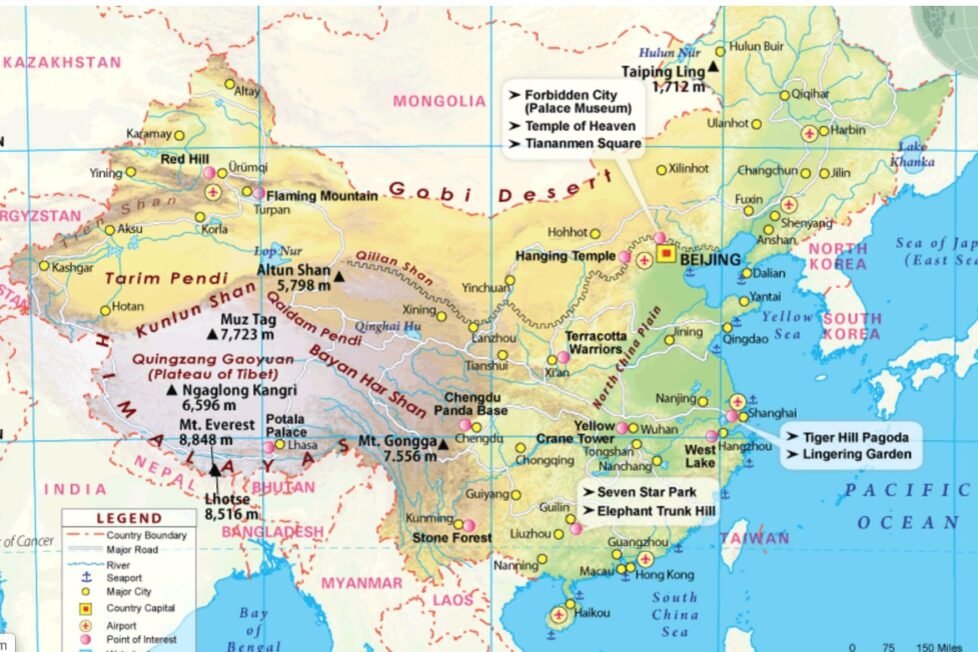

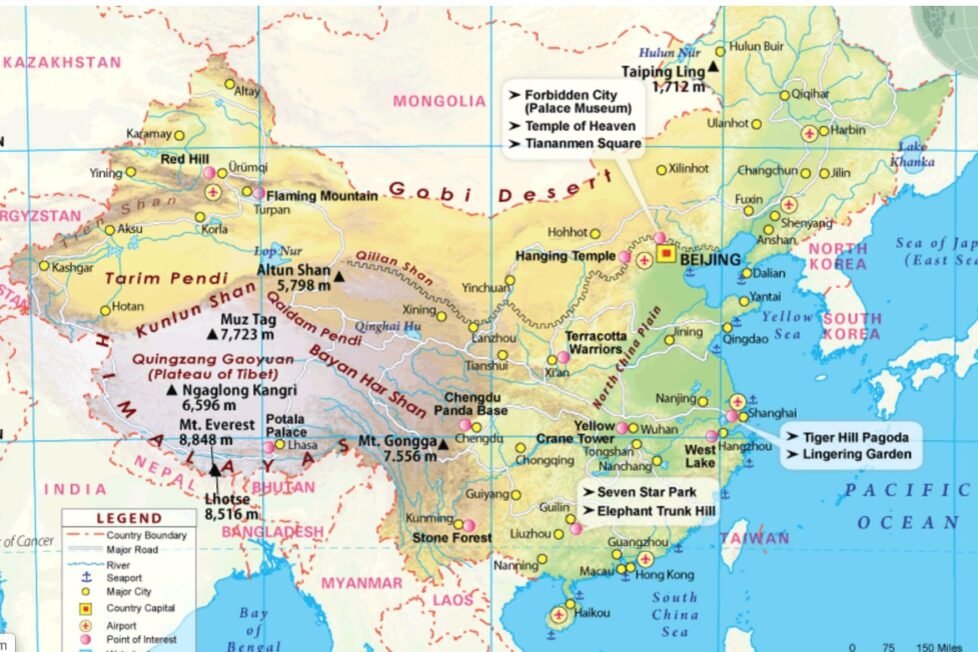

China, thus, appears through the antiquity as a smug self-sufficient power, which had astonishing geographical diversity under it — from the cold deserts of Siberia and Mongolia to the tropics of the Pearl River Delta, from the ocean in its east to the western trading town of Kashgar and from the below-sea-level Turpan to the forbidding mountains of Tibet, or Xijang. Some of these territories broke away from time to time, but for the larger part of the last two millennia and a quarter remained under the Central Chinese authority. Under Mao, the regime was Communist, but the underpinning of even Mao’s ideology was always the Middle Kingdom superiority.

After Mao, this complex has become all the more dominant, so much so that Communism today only helps the Chinese central authority to function verily as the ancient Emperor did. There is little Communism left in China, except its utilitarian value in providing an authoritarian party organisation for the important purpose of controlling the grassroots. It’s only China’s billion-plus largely middle-to-below-middle-income population which tempers this into realistic strategy.

In his seminal book On China, Henry Kissinger writes:

“The splendid isolation of China nurtured a particular Chinese self-perception. Chinese elites grew accustomed to the notion that China was unique — not just ‘a great civilization among others’ — but as the civilization itself”.

Accordingly, he quotes Lucian Pye, “China remains a civilization pretending to be a nation-state”. Thus, Kissinger writes,

“China was considered the centre of the world, the ‘Middle Kingdom’, and other societies were considered gradations from it. As the Chinese saw it, a host of lesser states that imbibed the Chinese culture and paid tribute to it was considered the natural order of the universe”.

Kissinger also writes that the traditional cosmology endured despite catastrophes and centuries-long periods of political decay. Even when China was weak or divided, its centrality remained the touchstone of regional legitimacy; aspirants, both Chinese and foreign, vied to unify or conquer it, then ruled from the Chinese capital without challenging the basic premise that it was the centre of the universe.

As Mao had feared, the Chinese DNA had reasserted itself. Confronting the new challenges of the twenty-first century, and in a world where Leninism had collapsed, Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao turned to traditional wisdom. They described their reform aspirations not in terms of the utopian visions of Mao’s continuous revolution, but by the goal of building a “xiaokang” (“moderately well-off”) society — a term with distinctly Confucian connotations.3 They oversaw a revival of the study of Confucius in Chinese schools and a celebration of his legacy in popular culture. And they enlisted Confucius as a source of Chinese soft power on the world stage — in the official “Confucius Institutes” established in cities worldwide, and in the 2008 Beijing Olympics opening ceremony, which featured a contingent of traditional Confucian scholars. In a dramatic symbolic move, in January 2011, China marked the rehabilitation of the ancient moral philosopher by installing a statue of Confucius at the center of the Chinese capital, Tiananmen Square, within sight of Mao’s mausoleum — the only other personality so honored.

Given this background, we can analyse why China has acted with such peremptory arrogance and unconcern to the spread of the infection worldwide, and to the 40000 plus deaths.

Firstly, since the Middle Kingdom can do no wrong, it must not admit its mistakes to the world. The CCP (Communist Party of China) authoritarianism and propaganda machinery are merely reinforcements of this central thinking process, and not the prime movers.

Secondly, the international order is supposed to be naturally subservient to the Middle Kingdom, hence their objections have no validity, legitimacy, or currency in the scheme of things.

Thirdly, since it is incumbent on the Middle Kingdom to keep testing the limits of its powers, the pandemic is yet another tool with which to test this power.

Fourthly, the present international order is not yet subservient to the Middle Kingdom, so every crisis must be used to shape it in China’s own image.

Fifthly, it gives China a unique chance to push for a higher status in the international order by pushing the United States down, and by overawing the smaller countries.

So, I am not at all surprised at China pushing back militarily at all its neighbours in order to suppress the criticism. The ‘Middle Kingdom’ is an exalted being, it can do no wrong. All those who criticise it must suffer for their comeuppance.

Sun Tzu had said that ‘all warfare is based on deception’, and China is treating the Wuhan Virus outbreak as a ‘war by other means’, hence nobody should mind the deception.

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text.