Rothschild of the East and Opium trade (Part-1)

They built a multi-continental corporate empire while making friends with and confidants of the British aristocracy and royal family. However, the Sassoon family originated in Baghdad, not in London, Paris, or New York, and made its millions by trading in opium, cotton, tea, and silk.

In his book, “The Sassoons: The Great Global Merchants and the Making of an Empire,” history professor Joseph Sassoon describes the family’s stratospheric rise and equally dramatic fall in engrossing detail.

David, the dynasty’s founding father, fled Ottoman Baghdad for Iran in the late 1820s, setting the stage for the narrative. David, the long-serving son of Sheikh Sassoon ben Saleh, a former chief treasurer to the city’s pashas, had been threatened and kidnapped by Baghdad’s infamously unscrupulous and corrupt ruler. Soon after, the elderly Sheikh, formerly referred to as “the most prominent Jew in Baghdad,” joined him, capping the family’s spectacular fall from glory.

Joseph Sassoon felt a kinship to his distant relatives after hearing about their departure from Baghdad, which was echoed by his own family’s escape from the Iraqi capital during Saddam Hussein’s ruthless regime. The Sheikh’s passing in 1830 accelerated David and his young family’s move to Bombay, where British rule offered safety and the government took a tolerant position toward the city’s Jewish population.

David was fortunate since Bombay, the rapidly expanding commercial jewel in the crown of western India, depending on the trade of opium and cotton for its prosperity. He also brought with him his father’s well-built network of connections among commercial families throughout the Ottoman Empire and Iran when he arrived in the city.

But David was also talented. He established long-lasting and permanent connections of trust and confidence among people with whom the family conducted business because, as Sassoon puts it, he considered a good reputation to be a “priceless asset.” His two oldest boys, Abdallah and Elias, were taught this lesson, and it served as the foundation for the family’s future commercial success.

David’s proficiency in Arabic, Hebrew, Turkish, and Persian quickly expanded upon his arrival in Bombay, and he spent countless hours getting to know the traders and agents at the city’s cotton exchange while attentively following global events that would have an impact on prices.

David started out as a textile trader and started to rise steadily but cautiously. Before he was acknowledged as one of the key figures in the Arab-Jewish trading community, it would be more than ten years. Another lesson David wanted to teach his sons was that a firm should be distinguished by a careful evaluation of risk and an avoidance of speculating.

David used both his political and business acumen. David allied himself closely with British imperial interests from the moment he arrived in Bombay, sharing his appreciation for the value of free trade and enterprise.

Elias’ crucial role serves as an example of how David created a true family business. There was plenty of action with 14 kids throughout 39 years of paternity. He instilled in his boys a business education while also urging them to explore, respect other cultures, and develop independence. He was strict yet kind.

In the meantime, the Sassoon company advanced thanks to the revenues from opium, which rose to become the most valuable traded commodity in the world, especially in the three decades following 1860. Local company divisions such as “House of Bombay” or “House of Shanghai,” run by David’s sons, were found. Silver and gold, silks, gums and spices, opium and cotton, wool and wheat – whatever travels over water or land feels the hand of Sassoon or bears his mark, according to one opponent.

The success of the company was based on its ability to produce high-quality goods, its flexibility due to a variety of suppliers and trading locations, and its reputation for being honest with customers. David’s unchallenged power and the family’s shared sense of purpose both contributed to this.

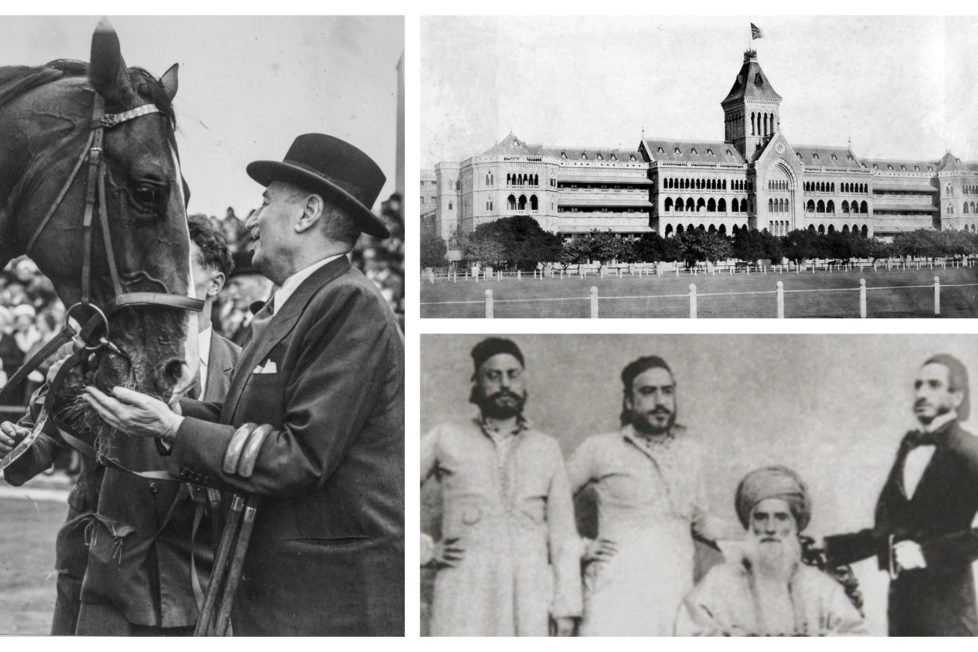

Epic levels of philanthropy were paired with business savvy: each trade, whether successful or not, had a quarter percent charitable surcharge, or tzedakah, recorded in branch ledgers. David started three schools in Bombay: one for females, one for boys, and one for young people from disadvantaged backgrounds. Later, the famed Sassoon Mechanics’ Institute, hospitals, and libraries would be added.

In the 1857 Rebellion, David offered the British “the assistance of the whole Hebrew community” of Bombay, and his financial success, devotion, and philanthropy were noted. He received British citizenship in 1853 as thanks for his services to the Empire (ironically, his English was poor and he signed his oath of allegiance to Queen Victoria in Hebrew). More awards followed, and in 1859 500 guests celebrated Britain’s decision to exercise a more direct form of control over its treasured imperial territory in his residence, San Souci, located in one of Bombay’s wealthiest neighborhoods.

David’s death at his residence in Pune in 1864 at the age of 71 proved catastrophic, if not fatal, similar to how many empires were held together by the glue of a revered and dominant individual. He designated Abdallah as his successor and instructed his other children to “respect and follow my said eldest son,” despite the fact that the succession had never been addressed. Elias, who had led the company’s operations in China and had made significant contributions, was only mentioned once.

Once David was no longer around to maintain a lid on things, the healthy element of competition amongst the company’s many houses—and brothers—soon started to curdle into fighting, finger-pointing, and animosity. Three years after the founder’s passing, the company split in two: Elias ran E.D. Sassoon & Co., and Abdallah continued to lead David Sassoon & Co.

Even if there were still family ties, no slack was taken in business. Abdallah was furious about his brother’s accomplishments, but Elias’s maxim, “Wherever David Sassoon & Co are, we will be; whatever they trade, we can trade,” guided the company even after his untimely death at age 60 in 1880.

The company survived the cotton market downturn and financial crisis that shook India in the middle of the 1860s because of David’s choice to invest in real estate, insurance, and banking, and it went on to rank among the top international traders. With his “combination of risk and innovation,” as Sassoon puts it, Abdallah helped the company reach new heights of prosperity. Opium, cotton, and textiles continued to contribute to its strong financial position, but new investments—in a syndicate of American railroad companies, Hungary’s national debt, banks, and real estate—keep moving forward.

Abdallah pursued David’s strategy of maintaining a close relationship with the British in various ways. Abdallah started to focus more on the west even though he was a familiar face on the Bombay social scene, a member of the city’s legislative council, and the governor’s advisor on construction and educational initiatives. The British bestowed additional decorations on Sir Albert Abdallah when he was knighted in 1872, making him known as Sir Albert. The following year, Abdallah became the first Jew to earn the Freedom of the City of London. Albert relocated permanently to London in 1874, the most significant commercial hub on earth and the imperial capital.

Another of David’s sons, Sassoon David Sassoon, had already blazed the Sassoon road to Britain nearly two decades prior. Sassoon David, the “pioneer of the House of Sassoon in England,” oversaw the growth of the company in the UK. His brother Reuben soon followed. The purchase of a sizable estate at Ashley Park in the wealthy home counties of the capital, according to Sassoon, became “the most prominent symbol of both the family’s wealth and their changing aspirations for years to come.” He led the family’s ascent to the top echelons of London’s financial world.

Unsurprisingly, Albert was rapidly accepted into the upper strata of British society after arriving in London. He undoubtedly showed his value. Up instance, Albert arranged for a night of “glittering entertainment” at the Empire Theatre when the Shah of Iran visited London in the late 1880s. The British government, which saw Persia as strategically significant to the Empire, as well as the royal guest and his host, the Prince of Wales (the future King, Edward VII), were delighted by the action. Soon after, in 1890, Queen Victoria bestowed a baronetcy as compensation on Albert.

Albert was not the only person in Europe who had cordial ties to the nobility and royalty, both in the UK and elsewhere. His half-brother Arthur wed Eugenie Louise Perugia, a long-established Italian Jewish family, in 1873. As she became widely known, “Mrs. Arthur” was a fixture of the London social scene and frequently appeared in Queen Victoria’s journals. As soon as Edward, the son of Albert, wed Aline, the daughter of Baron Gustave de Rothschild of Paris, in 1887, the Sassoons also became related to the Rothschilds by marriage. Later, Edward was chosen to serve as the MP for Hythe, a Kent constituency that had previously elected Meyer de Rothschild.

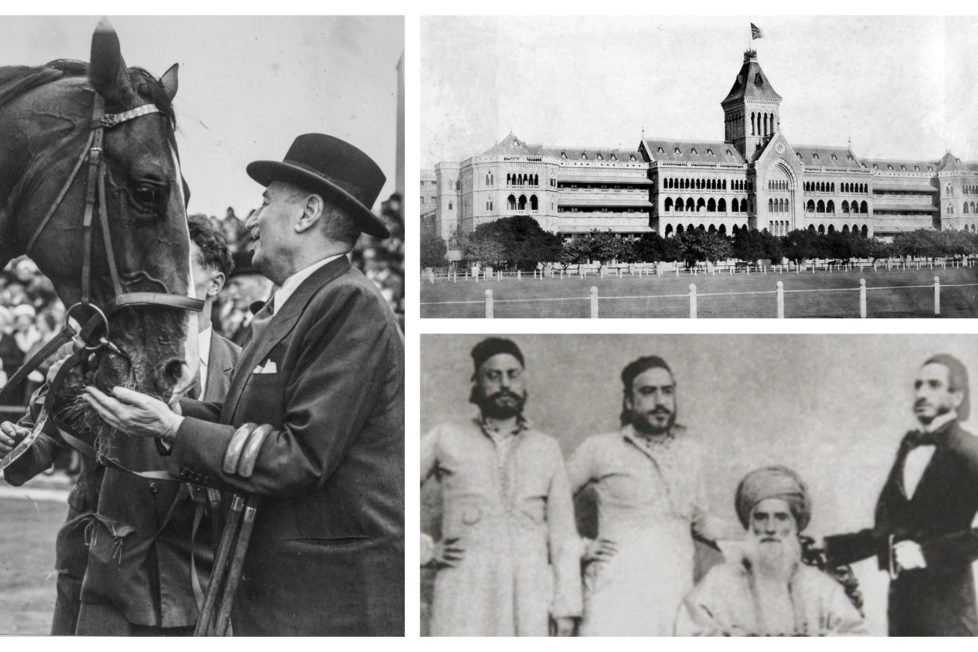

The royal family was most familiar with Reuben and Arthur, two of Albert’s brothers. They had a passion for horse racing, shooting, and hunting in common with the Prince of Wales, Queen Victoria’s eldest son. The “gay parties” that Arthur and his wife hosted at their estate in the Scottish Highlands were loved by Edward and his “Marlborough House set” of stylish friends. As the Prince’s “unofficial bookie” and “controller of cash for his hobbies,” Reuben gained notoriety.

While his half-brother Suleiman, who was stationed in Bombay, managed the store in the East primarily, Albert never let his new life in Britain divert him from his duties to the company. Even amid the economic downturn that spread from London throughout the globe to the Sassoon family’s wealth, they continued to prosper.

However, Albert’s passing in 1896 signaled “the beginning of the end” for the business, according to Sassoon. On the horizon, there were already storm clouds. Despite the fact that opium income had started to decline to start in the 1890s, the Sassoons did not effectively diversify their business. Additionally, even though they were able to resist religious and political pressure in Britain to outlaw this “evil trade,” the signs were already there as the new century got underway. For instance, Britain and India, and China agreed in 1907 that opium exports and cultivation would be prohibited within ten years. British policy was further strengthened six years later. Nevertheless, both Sassoon businesses carried on selling the medicine in an effort to make as much money as possible from the now-discredited business.

Sassoon advises against just using a modern moral framework to evaluate the family’s involvement in the opium trade. He makes the point that the medication was acceptable and freely available in pharmacies as a means of pain alleviation, and that the financial press had published the drug’s price. The family should have “fallen out” of the dying trade, in his opinion, much earlier than it did, both for commercial reasons and because “staying around until the last box” was sold would have been “squalid.”

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text.