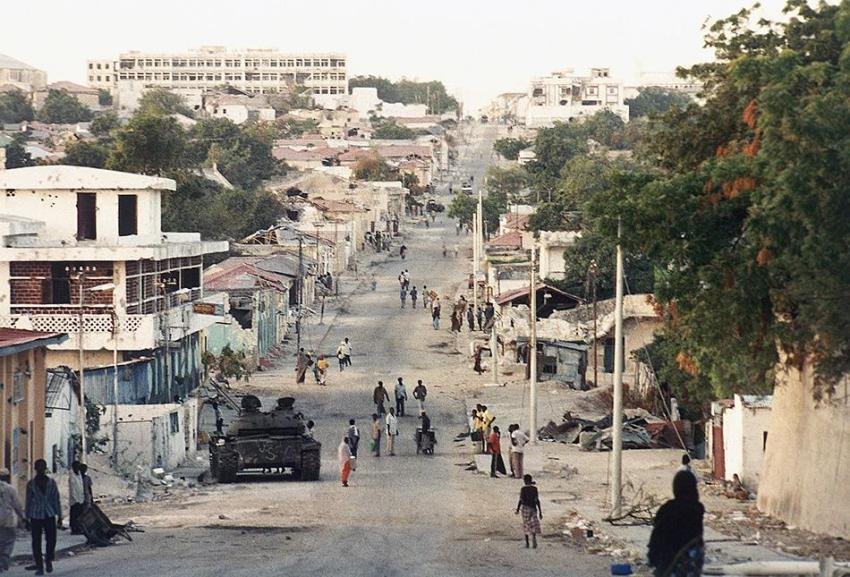

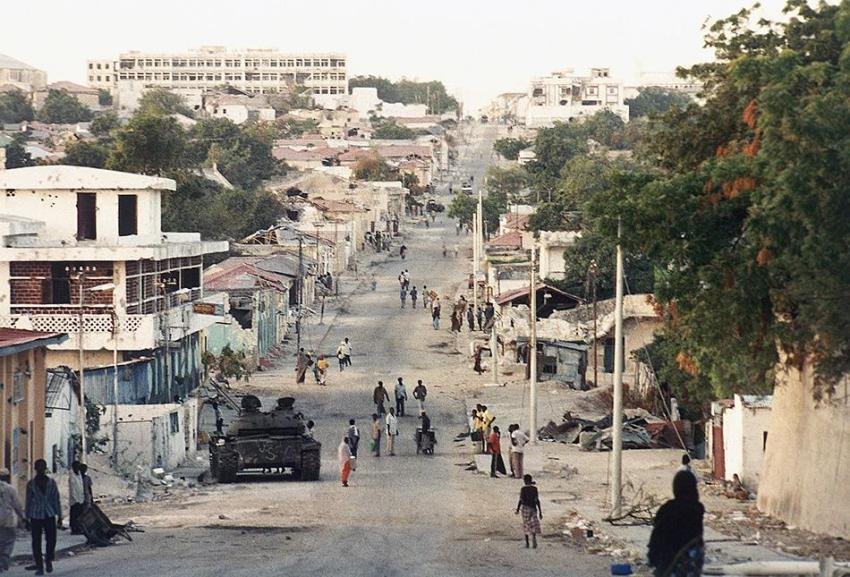

When Pakistan Army shot 70 Somalis!

In Mogadishu, Somalia, on June 13, 1993, a machine gun-wielding member of the Pakistani contingent of UNOSOM II opened fire on a throng of protesters, shooting about 70 Somalis. As a result, 20 were dead while 50 were injured including women and children. The shooting happened a week after the attack on the Pakistanis on June 5, 1993.

Intervention by the UN in Somalia (1992-1995)

The murders contributed to an anti-United Nations feeling that was rising among Somali residents, which General Mohamed Farah Aidid and the Somali National Alliance would capitalize on.

The Pakistani component of UNOSOM II lost 25 of its peacekeepers on June 5, 1993, in a conflict with Somali militants and civilians, making it the worst day for UN forces since the Congo in 1961. After the murder, a number of U.N. and Western diplomats voiced concern that some Pakistanis who were outraged by the killing of their fellow countrymen may stage an uncontrollable protest or seek retribution.

A minibus transporting unarmed civilians traveling on Suuqa Hoola Road was fired upon by Pakistani UNOSOM forces at 6 o’clock on the day after the 5 June event, purportedly resulting in the deaths of four passengers and other injuries.

On June 12, a few people were protesting UNOSOM military operations in Mogadishu when Pakistani forces opened fire on them as they marched toward UN offices on Afgoy Road. A ten-year-old in the mob made an “obscene gesture” toward the soldiers as the protesters passed the Pakistanis and started throwing stones. The Pakistani position immediately responded by opening fire, just missing the ten-year-old but killing a man and a woman, with some witnesses also reporting a third casualty.

On June 12, 1993, after the first night of the AC-130 attacks in Mogadishu, anti-UNOSOM demonstrations broke out all around the city.

Around 10:30 on Sunday, June 13, 3,000 to 4,000 Somalis marched in protest of UNOSOM military operations close to a Pakistani position. According to testimonies from Somali and foreign media, the military fired a belt-fed machine gun from a sandbagged post on a building rooftop overlooking the streets without giving any prior notice to the gathering.

Paul Watson, a reporter for the Toronto Star who attended the demonstration, claimed that “Prior to the Pakistanis starting to shoot, I don’t remember hearing a shot. They shot several hundred bullets.” A 10-year-old bystander was shot in the head, and Hussein Ali Ibrahim, a 2-year-old boy, was killed by a machine gun bullet to the belly while he was half a mile away. According to the New York Times, at least five victims were hiding behind cars at the time of their deaths. According to Washington Post reporter Keith Richburg, the pattern of hundreds of shots fired indicated that the Pakistanis may have started shooting in areas where people were escaping by opening fire down numerous streets.

Several bullets struck the exterior of the hotel where journalists were staying, and one of them tore a hole in the wall just before narrowly missing an Associated Press reporter using the shower.

Photographer Alexander Joe for Agence France-Presse claims that after the incident, a Pakistani U.N. convoy drove very close to children on the street who had been hurt and begged them for assistance before ignoring them.

Following the killing, Somalis surrounded war correspondent Scott Peterson and The Guardian reporter Mark Huband, telling them they would not be allowed to go until they had recovered the victims’ bodies because they thought UNOSOM soldiers would not dare shoot at white Westerners. The two reporters would pick up the injured and deceased and transport them to Banadir Hospital.

U.N. account of the incident

Brig. Gen. Ikram ul-Hasan, the commander of Pakistani forces in Somalia, asserted that Somali gunmen present at the demonstration had fired at his troops. He implied further that Somali militants would exploit women and children as human shields. Ikram further claimed that, contrary to the reports of Somali and international journalist witnesses who claimed not to have heard any warnings from the Pakistanis, he thought his troops had first asked the gathering to disperse before firing warning shots.

Retired U.S. Adm. Jonathan Howe, the U.N. Secretary-special General’s envoy to Somalia, justified Pakistan’s actions in an interview with the BBC hours after the killing. In striking comparison to journalist and Somali eyewitness accounts, he claimed that demonstrators had attacked Pakistani forces while using women and children as human shields and that Pakistan had fired warning shots.

The killing of civilians by peacekeepers on June 12 and 13 heightened Somalians’ hostility toward UNOSOM II. Many U.N. officials and diplomats were horrified by the sight of Somali civilians being shot at point-blank range by UNOSOM troops, and many saw this as a serious setback to the organization’s reputation as a force for peace among the Somali people. The following day, on June 14, Doctors Without Borders replied to the killings with a press release criticizing the UNOSOM II forces’ disproportionate use of force, and the organization’s president referred to the episode as “monstrous.”

Brig. Gen. Ikram ul-Hasan, the commander of Pakistani forces in Somalia, refuted claims made by journalists that his troops were seeking revenge for the 5 June 1993 ambush, while American ambassador to the UN Madeleine Albright officially defended the Pakistanis’ actions as carried out in self-defense.

A few days after the shooting, US President Bill Clinton held a news conference in which he harshly denounced Aidid for killing UNOSOM soldiers but did not denounce the killings of Somali civilians by U.N. forces—an episode that did not go unnoticed in Mogadishu. The executions contributed to an anti-United Nations feeling that was already present in Somalia, which the Somali National Alliance exploited.

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text.