Mizo or Kuki or Chin? A Brief History of Mizoram

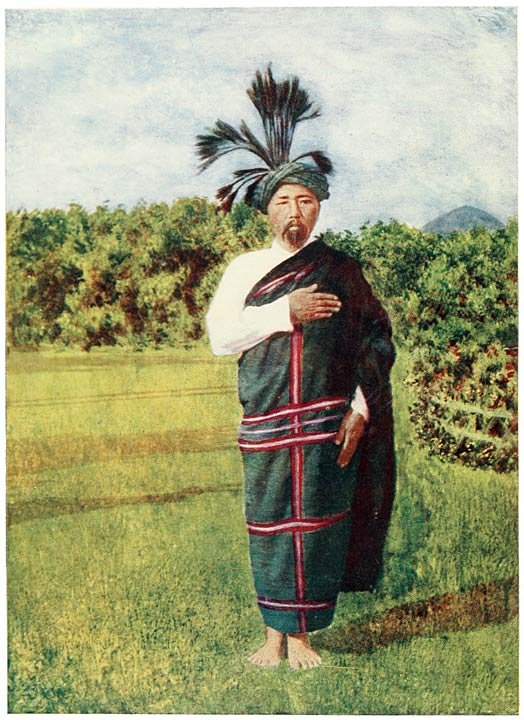

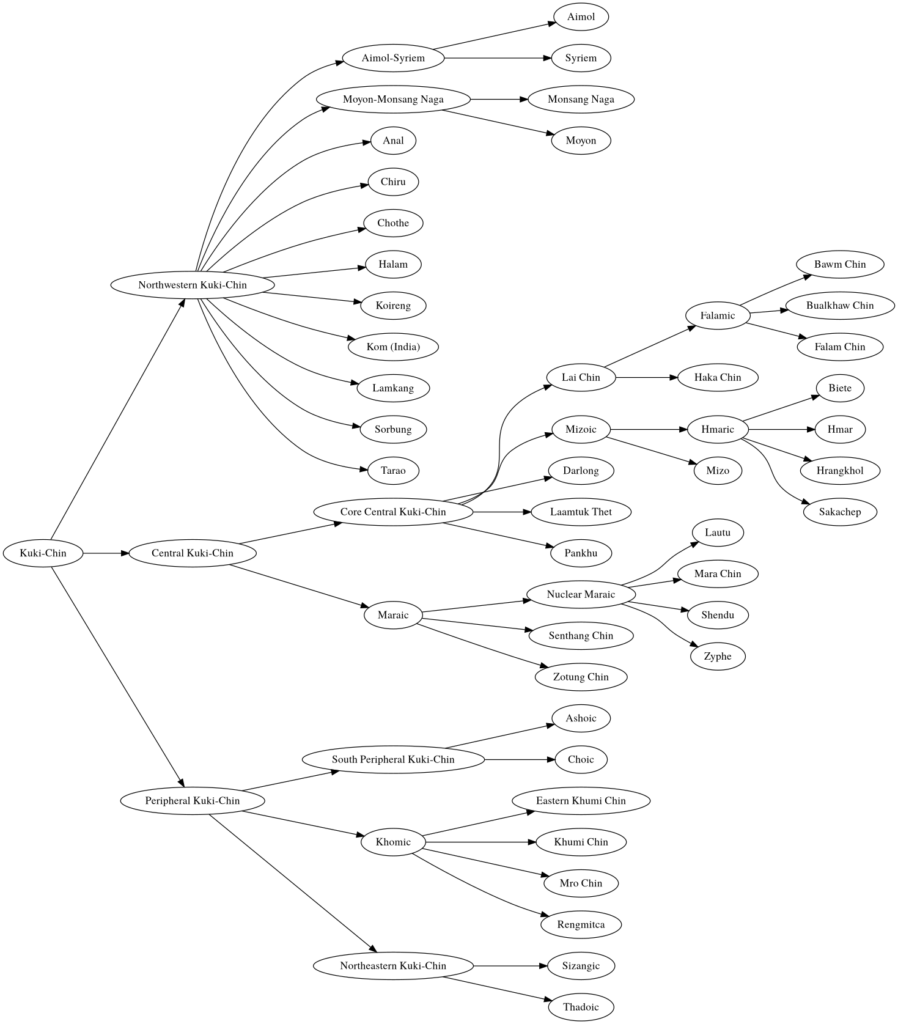

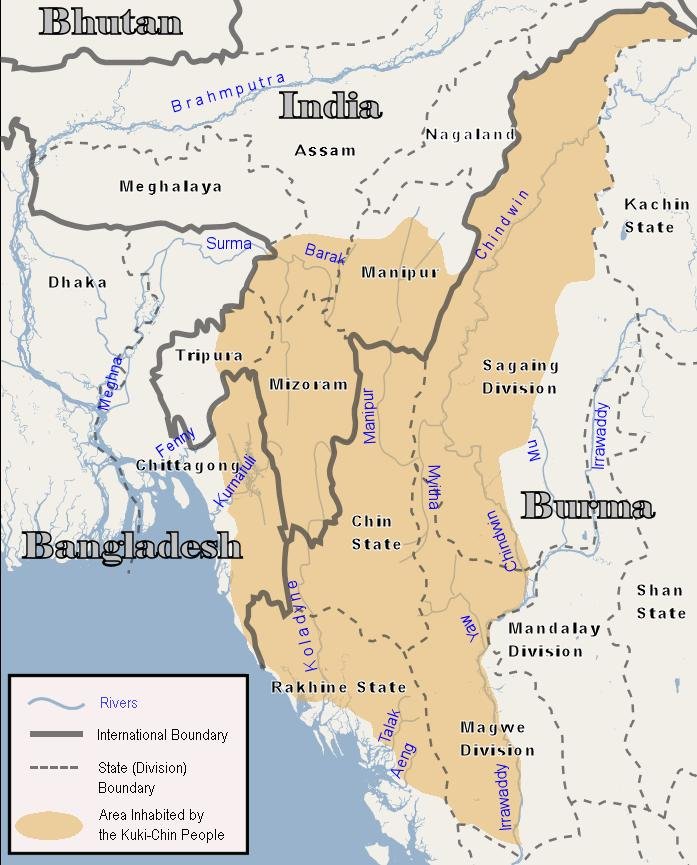

It is not widely known that something called Mizo doesn't exist. It's an artificial construct introduced as a national identity of the Kuki/Chin tribes residing in Mizoram who converted to Christianity and are ready to lose their identity to become a part of Lushai Tribe. Lushei tribe which entered India in late 1700s is one of the last in the wave of tribes entering from Yunnan into North East India and on it's wake, the other tribes residing in Lushai Hills fled further towards Cachar and Manipur. The introduction of Christianity made them a unified mass with a common identity which is still a major reason for strife between Mizos and Bru, the older and more original residents in Mizoram.