Sri Lanka Economic Crisis: Step-By-Step Tutorial on Inviting Bankruptcy and Economic Ruin.

“Gotta Go, Gotabaya,” “Gotta Go, Gotabaya,” and “Gotta Go, Gotabaya,” are the slogans that are filling the air of Columbo and every city of Sri Lanka these days.

History is witnessing the worst protest since Sri Lanka’s independence where thousands of citizens have taken to the streets since the nation ran out of money for vital imports and had seen the prices of essential commodities skyrocketing and caused acute shortages of fuel, medicines, and electricity.

The powerful Rajapaksa clan has ruled Sri Lanka for decades and came back, after a brief spell out of power, in 2019 when Gotabaya was elected president. Although troubled by corruption allegations, the current dissatisfaction stems from economic mismanagement.

Gotabaya was once popular for ending a decades-long civil war in 2009, with a bloody bombing campaign against Tamil separatists.

Hundreds of thousands of people came out on the streets of Sri Lanka demanding the ouster of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, defying a state of emergency.

Protesters are demanding the resignation of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa as they blame his policies for the crisis, but the President is refusing to quit.

With every passing day, Sri Lanka’s economic difficulties continue to worsen. Food prices are soaring, and its coffers are running empty. The island nation is already on the verge of a “humanitarian crisis,” according to the United Nations Development Programme.

For the past few weeks, many Sri Lankans have been forced to wait in long queues in the capital of Colombo and its suburbs to obtain fuel for their motorbikes and vehicles. Some fuel stations remained closed as new supplies are not received.

Over the last few weeks, Sri Lankans had experienced several sporadic power failures.

Sri Lanka’s Public Utilities Commission said “Every day the country’s grid will be shut for four and a half hours”. Electricity will be switched off on a rotating basis between regions between 8:30 a.m. and 10:30 p.m., according to officials[1].

The regulatory body said the state-owned Ceylon Electricity Board had requested permission for the cuts as fuel shortages had caused the loss of about 700 MW to the national grid.

Commission’s chairman Janaka Ratnayake said the “shortage of fuel is causing this issue” while adding that “we are having a fuel crisis not an electricity crisis.”

Rampant inflation and shortages of imported food, fuel, and medicines have led to weeks of sporadically violent protests.

Economic Critics say the roots of the crisis, the worst in several decades in south Asian nations, lie in economic mismanagement by successive governments that created and sustained a twin deficit, a budget shortfall alongside a current account deficit.

“Sri Lanka is a classic twin deficits economy,” said a 2019 Asian Development Bank working paper[2].

“Twin deficits signal that a country’s national expenditure exceeds its national income, and that its production of tradable goods and services is inadequate.”

But the current crisis was accelerated by deep tax cuts promised by Rajapaksa during a 2019 election campaign that was enacted months before the COVID-19 pandemic, which wiped out every part of Sri Lanka’s economy.

With Sri Lanka’s lucrative tourism industry and foreign workers’ remittances sapped by the pandemic, credit rating agencies moved to downgrade Sri Lanka and effectively locked it out of international capital markets.

In turn, Sri Lanka’s debt management program, which depended on accessing those markets, derailed, and foreign exchange reserves plummeted by almost 70 percent in two years.

The Rajapaksa government’s decision to ban all chemical fertilizers in 2021, a move that was later reversed, also hit the country’s farm sector and triggered a drop in the critical rice crop.

According to some sources, the rating firm Fitch cut Sri Lanka’s credit rating last month due to concerns of sovereign default on the country’s $26 billion foreign debt[3].

Early this year, the Census and Statistics Department (CSD) released data showing that the country’s GDP declined by 1.5 percent during the third quarter of 2021.

Already hit hard by the pandemic and short of revenue, the island nation is now also critically short of foreign exchange and has approached the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for an emergency bailout.

Sri Lanka faces one of its worst economic crises, with foreign reserves down to around $1.6 billion, barely enough for a few weeks of imports. It also has foreign debt obligations exceeding $7 billion in 2022, including repayment of bonds worth $500 million in January and $1 billion in July.

Sri Lanka faces one of its worst economic crises, with foreign reserves down to around $1.6 billion, barely enough for a few weeks of imports. It also has foreign debt obligations exceeding $7 billion in 2022, including repayment of bonds worth $500 million in January and $1 billion in July.

The pandemic has dealt a heavy blow to Sri Lanka’s economy, which depends heavily on tourism and trade, with the government estimating a loss of $14 billion in the last two years.

According to World Bank estimates, five lakh people in Sri Lanka have dropped below the poverty line since the epidemic hit, which the bank termed a “major setback comparable to five years’ worth of development”[3].

The economy had estimated to have contracted by 1.5 percent in July-September 2021, according to the central bank. Inflation also surged to 12.1 percent in December 2021.

The declining foreign reserves are partly blamed on infrastructure projects built with Chinese loans that don’t make money. China loaned money to build a seaport and airport in the southern Hambantota district, in addition to a wide network of roads.

Central Bank figures show that current Chinese loans to Sri Lanka total around $3.38 billion, not including loans to state-owned businesses, which are accounted for separately and thought to be substantial.

Amidst the economic slump, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi visited Sri Lanka and the President Gotabaya Rajapaksa told him that “it would be “a great relief to the country if attention could be paid to restructuring the debt repayments as a solution to the economic crisis that has arisen in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic,” according to a statement from his office[4].

Rajapaksa asked Wang for a concessionary credit facility for imports so that industries can run without disruption, the statement said. He also requested assistance to enable Chinese tourists to travel to Sri Lanka within a secure bubble.

It will be right to mention that China’s Belt and Road Initiative, massive loans, and economic profligacy would propel them to wealth will be shocked if they take even a cursory glance at Sri Lanka’s financial troubles.

When neighbor Sri Lanka had been going through a severe economic crisis, New Delhi provided a series of financial packages to Colombo so that it can meet some of the more immediate needs and help stabilize its domestic economy.

PM Modi has conveyed to Sri Lankan Finance Minister Basil Rajapaksa, who has visited India twice in the last couple of months, that India would always stand with the island nation as it occupies a central role in New Delhi’s “Neighborhood First Policy.”

“Had a good meeting with Sri Lanka’s Finance Minister @RealBRajapaksa. Glad to see our economic partnership strengthen and investments from India grow,” PM Modi had tweeted[5].

In November 2021, India had given 100 tons of nano nitrogen liquid fertilizers to Sri Lanka as their government stopped the import of chemical fertilizers.

In February, New Delhi provided a short-term loan of USD 500 million to Colombo for the purchase of petroleum products through the Ministry of Energy and the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation on behalf of the Government of Sri Lanka.

The total fuel delivered to the people of Sri Lanka, over the last couple of days, amounts to nearly 200,000 MT including a consignment of 40,000 MT, by Indian Oil Corporation, outside the line of credit facility, in February 2022.

Energy Minister Gamini Lokuge thanked the Government of India for the fuel consignments.

In April 2022, As New Delhi had again provided financial assistance to Colombo, India has announced another USD 1 billion as a credit to Sri Lanka to help shore up the sinking economy of the island nation. The USD 1 billion line of credit to Colombo will help in keeping their food prices and fuel costs under check.

India shipped the first rice consignment under this credit facility. The rice shipments could help Colombo bring down rice prices, which have doubled in a year, adding fuel to the unrest. “Rice loading has started in southern ports,” said BV Krishna Rao, managing director of Pattabhi Agro Foods, which is supplying rice to Sri Lanka State Trading (General) Corp under the Indian Credit Facility Agreement[5].

These facilities, negotiated and concluded within a matter of weeks, have proved to be the lifeline for the people of Sri Lanka.

Besides, RBI has extended a currency swap of US dollars 400 million and deferred payments owed by the Central Bank of Sri Lanka owed to RBI under the Asian Clearance Union worth several hundred million dollars.

India’s prompt assistance to the people of Sri Lanka at this hour has been appreciated by all sections of the Sri Lankan society.

Several state hospitals issued letters stating that surgeries and lab tests would be suspended due to the prevailing drug shortage. The Peradeniya Hospital for instance announced its suspension of surgeries, but following Indian Minister of External Affairs Dr. S Jaishankar’s intervention, the hospital resumed surgeries.

Addressing the Asia Economic Dialogue 2022, Health Minister of Sri Lanka, Keheliya Rambukwella said, “We extend our gratitude to India, particularly for the donation of the first 500,000 vaccines.”

Elaborating on the economic handling during the COVID-19 pandemic, the minister said, “We are getting assistance from many areas and our neighbor India is always at hand and has been helping us throughout.”

In April 2022, Asian giant, India have already committed billions of dollars in financial support and had again willing to commit up to another $2 billion in financial assistance to Sri Lanka while also supporting the island nation with food and fuel, five sources told Reuters, as New Delhi tries to regain ground lost to China in recent years.

“We are definitely looking to help them out and are willing to offer more swap lines and loans,” said an Indian source aware of various discussions with Sri Lanka.

Another source familiar with Sri Lanka’s thinking said it was seeking India’s help to roll over some $2 billion in dues, such as those owed to the South Asia-focused Asian Clearing Union. The source said the response had been positive from India.

India has so far committed $1.9 billion to Sri Lanka in loans, credit lines, and currency swaps. Sri Lanka has also sought another $500 million credit line for fuel.

Early this week, Sri Lanka extended a credit line with India by $200 million in order to procure emergency fuel stocks, the country’s power and energy minister said.

Colombo was also in talks with New Delhi overextending the credit line by an additional $500 million, minister Kanchana Wijesekera told a news conference, with four fuel shipments due to arrive in May.

The Sri-Lankan cricketer has also thanked Modi Administration for the timely help. “You know as always as a neighbor, the big brother next to our country has been helping us… We are very grateful to the Indian government and the Prime Minister (Modi),” Jayasurya said.

Sri Lanka has already used $400 million, on multiple shipments in April, of the $500 million credit line extended by India earlier this year, Wijesekera said. Two fuel shipments will be paid for from the remaining funds in May.

“The Indian credit line was extended by $200 million recently and this will be utilized for four shipments in May. Talks are continuing for a further $500 million with India so in total, the credit line will be $1.2 billion,” Wijesekera said[6].

“We have made procurement plans till June but we still need to resolve how to find sufficient amounts of foreign exchange to make payments,” Wijesekera further added.

However, Sri Lanka is still facing payment challenges for fuel imports with the state-run Ceylon Petroleum Corporation (CPC) owing $235 million for shipments already received, while about $500 million more will be needed to pay for letters of credit maturing over the next six weeks, he added.

Sri Lanka will also need dollars to pay for crude oil shipments to supplement imports from India.

On his first visit to India since he was appointed last year, Sri Lankan Foreign Minister G.L. Peiris said that India’s support has made a “world of difference” to Sri Lanka’s economic situation. “There’s no doubt whatsoever that Indian support at this critical juncture has made a world of difference. It has helped us to tide over the immediate difficulties which were obviously acute, Rambukwella added. (ANI)

Many West fed Analysts are comparing Sri Lanka protests with Arab Springs and are naming it as the Sri Lankan version of the Arab Spring.

The Arab Spring refers to a series of protests that began with the self-immolation of a vendor in Tunisia in 2010 and spread across several countries in the Arab world such as Egypt, Libya, and Syria against authoritarianism, corruption, and poverty. As many as four autocrats, including Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak, were ousted during the Arab Spring[7].

Like the crisis in Sri Lanka, the Arab Spring was also triggered by economic stagnation and corruption in Tunisia, said Chulanee Attanayake, a research fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies at the National University of Singapore.

“Sri Lanka is also witnessing anti-government protests in response to an economic downturn, rising inflation, and shortage of essential goods. Similar slogans as during the Arab Spring are also being used,” he said.

“It’s the Arab Spring in Sri Lanka. It’s a perfect match with the pattern of an Arab Spring: a people’s uprising to end authoritarian rule, economic mismanagement, and family rule, and install democracy,” Asanga Abeyagoonasekera, a senior fellow at Millennium Project in Washington, told CNBC.

However, Fung Siu, principal economist for Asia with the Economic Intelligence Unit, a think tank, disagreed with the Arab Spring parallel.

“Triggers for the Arab Spring were years in the making, while discontent in Sri Lanka can be traced back to the onset of the pandemic and bad policy choices,” she said[7].

For months, Rajapaksa’s administration and the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) resisted calls by experts and opposition leaders to seek help from the IMF despite rising risks.

But after oil prices soared in the wake of Russia’s special operations in Ukraine in late February, the government eventually drew up a plan to approach the IMF last month.

The IMF will initiate discussions with Sri Lankan authorities on a possible loan program in “coming days”, an IMF spokesman said on Thursday[2].

Sri Lanka has sought IMF bailouts 16 times in the past 56 years, second only to debt-ridden “Terror Heaven Country Pakistan”.

Before heading to the IMF, Sri Lanka steeply devalued its currency, further stoking inflation and adding to the pain of the public, many of whom are enduring hardship and long queues.

The IMF and World Bank, part of the Bretton Woods heritage, are the West’s main international financial institutions (IFI). Since 1944, the IMF and World Bank have been the crucial twin intergovernmental institutions shaping the world’s development and financial order.

These loans, however, come at a steep cost: implementing the IMF‘s economic policies. Here is a sample from the IMF Executive Board’s 2021 Article IV Consultation Statement:

Noting Sri Lanka’s low tax-to-GDP ratio, they saw scope for raising income tax and VAT rates and minimizing exemptions, complemented with revenue administration reform. Directors encouraged continued improvements to expenditure rationalization, budget formulation and execution, and the fiscal rule. They also encouraged the authorities to reform state-owned enterprises and adopt cost-recovery energy pricing.

History has witnessed that whenever any country runs into an economic crisis, it has looked to major International Financial Institutions (IFI) like International Monetary Bank (IMF), World Bank, etc., but the question is are these financial institutions trusty worthy?

In effect, the IFIs are the harbingers of neo-liberalization. They are also undemocratic, imposing conditions on foreign governments.

The IMF and World Bank are multilateral institutions, and in theory, there is the possibility to review the hierarchy of the international economic architecture through institutional reforms.

But in practice that is not happening.

The Western hegemony of the IFIs continues to represent the U.S. imperial project of global neoliberalism.

As W.D. Lakshman wrote all the way back in 1985:

Sri Lanka after 1977 has become yet one more laboratory for IMF-WB experimentation. These institutions, whose resources and policies are controlled by the developed countries of the West, probably sincerely believe that the free market, private enterprise, and capitalist system which proved effective in those countries in the advancement of the forces of production, will also be effective in the Third World.

Sri Lanka is a prime example of a Third World country led by a post-colonial elite that is using people as collateral for their power considerations. The island nation has been surrendered to international financial organizations and regional superpowers as a battleground for neoliberal destruction and as a vessel for geopolitical power considerations.

The idea of human rights of empowering people in the Global South at least is futile when the very international organizations ostensibly promoting human rights are also imposing their own political agenda on the country. In this context, human rights are easily sacrificed for financial power.

A United Nations assessment of World Bank policies provocatively concluded that the organization is “a human rights-free zone… It treats human rights more like an infectious disease than universal values and obligations.” IFI’s have chosen, willingly and deliberately, to engage in neocolonialism.

As Balakrishnan Rajagopal writes:

The colonial vestige of Europe and the United States appointing the heads of the Bretton Woods institutions even continues without challenge. Private markets – those which caused the worldwide financial meltdown, including bond traders, hedge funds, and, of course, credit rating agencies – are not governed by international law at all, but only by weak national regulators who lack competence and independence. We are back to business as usual[8].

The ones who suffer the most are the people of the Global South. It can be very well witnessed by the example of Sri Lanka; its people will have to bear the brunt of skyrocketing prices and shortages of essential products for a long time to come.

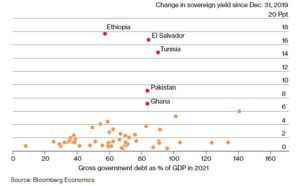

The cocktail of risks has already pushed Sri Lanka to the brink of default on its bonds. A handful of other emerging economies, from Pakistan and Tunisia to Ethiopia and Ghana, are in immediate danger of following suit, according to Bloomberg Economics.

Of course, the developing world’s commodity exporters stand to benefit from higher prices. Still, there are other troubles brewing, with a new Covid-19 outbreak locking down key cities in China, and growing angst that Europe and the U.S. will fall into recession.

Bloomberg Economics spotlights five countries where a mix of elevated debt and surging bond yields are creating default risks.

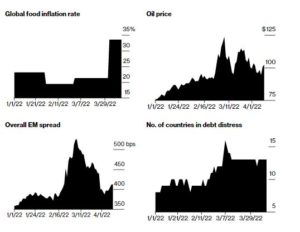

Turmoil triggered by rising food and energy prices is already gripping countries like Sri Lanka, Egypt, Pakistan, Tunisia, and Peru. It risks turning into a broader debt debacle and yet another threat to the world economy’s fragile recovery from the pandemic[9].

Bloomberg Economics, which keeps scorecards of the building risks for EM countries, puts Turkey and Egypt top of the list of major emerging markets exposed to “economic and financial spillovers” from the Ukraine war.

And it also ranks Tunisia, Ethiopia, Pakistan, Ghana, and El Salvador with large debt stocks and borrowing costs that have risen by more than 700 basis points since 2019 among countries in immediate danger of being unable to repay debts.

Compounding the danger is the most aggressive monetary tightening campaign the Federal Reserve has embarked on in two decades. Rising U.S. interest rates mean a jump in debt-servicing costs for developing nations — right after they borrowed billions to fight Covid-19 and tend to spur capital outflows.

And on top of it all: the stark reality is Russia’s operation in Ukraine, which is driving the latest food and energy shock, shows few signs of ending.

Robin Brooks, the chief economist at the Institute for International Finance, predicts the fallout from Russia’s Special operations will largely be limited to food and energy importers.

By contrast, the crises of the 1990s erupted in economies where capital had been pouring in, and its abrupt departure revealed flaws in corporate balance sheets. Even with risks rising because of an increasingly aggressive Fed, “I’m not as worried as others about skeletons in the closet,” he said.

But if that pandemic backdrop leaves emerging countries less vulnerable to capital outflows, the opposite is true when it comes to social tensions.

That’s one reason why it’s hard not to see something broader in the political and economic turmoil starting to hit the poorest corners of the global economy. Oxfam is warning that more than a quarter of a billion people could be pushed into extreme poverty this year.

[1] Sri Lanka Imposes Power Cuts as Cash Crisis Deepens – The Diplomat

[2] Explainer-How Sri Lanka’s economy spiralled into crisis By Reuters (investing.com)

[3] Sri Lanka Economic Crisis Reason, China Involvement, Solution (dmerharyana.org)

[4] Sri Lanka Seeks Chinese Debt Restructuring Amid Crisis – The Diplomat

[5] India providing financial package to Sri Lanka to help stabilise its economy – ThePrint

[6] Sri Lanka extends credit line with India as China voices support | Reuters

[7] Sri Lanka’s crisis follows similar pattern as Arab Spring, say analysts (cnbc.com)

[8] Sri Lanka and the Neocolonialism of the IMF – The Diplomat

[9] Sri Lanka’s Economic Crisis Is Warning Sign for Global Food, Fuel Struggles – Bloomberg

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text.